Visually Tim Burton is one of the most recognizable directors. Watching a Tim Burton film is like stepping into a macabre fairy tale with a mix of delightfully, deranged characters. His hellish city-scapes, abandoned amusement parks, haunted villages and houses, and creepy circuses are perfect settings for his mix of zany humor and horror. It’s often dark and disturbing, but you always get a sense Burton is reveling in his grim creations. For Burton, it’s the normal world, like suburbia, that is the true horror in his films.

Burton, who felt isolated and different in his childhood, turned to movies, especially the B-movies of Universal, Hammer Horror, and the mid-century sci-fi movies of directors like Roger Corman. While most audiences feared characters like The Wolfman and Frankenstein’s monster, Burton connected with them. He felt empathy for these characters who he viewed as misunderstood and attacked by others for just being different. As such, most of his movies are autobiographical in their explorations of themes of isolation and uniqueness.

They also became a medium for the director to express his own unique visual style. Whether it’s Beetlejuice, Edward Scissorhands, Batman, Sweeney Todd, Mars Attacks!, Dark Shadows, or Corpse Bride, Burton’s distinctive filmography bears the hallmarks of a visual style often defined as ‘Burtonesque’.

Set design, Gothic elements, and the way he plays with light and shadow are seen in everything from Batman to his live-action adaptation of Dumbo. Burton’s visual style is certainly unique, but nonetheless, the director is heavily influenced by some established art movements and cinematic styles. His style is eclectic, and it’s in the combination of different styles, that his style has become uniquely his own.

So, what are the distinct trademarks or visual conventions that make up his Burtonesque style? Let’s start with a quick video by Fandor.

This video works as a brief refresher of Burton’s images: nightmarish sets, scary clowns, and surreal visual humor. But let’s delve deeper into the origin of all this nightmarish zaniness.

Burtonesque Embraces German Expressionism

Anyone familiar with the Arts can immediately tell Burton’s films are rooted in German Expressionism. What began as a modern art movement in the 1920s, swept through art, cinema, and animation in Europe, and then onto America. The German movement originated during World War 1 and drew on psychoanalysis. A German Expressionist film explores themes of insanity, chaos, death, and fear, which is what the German people experienced as a reaction to the war. And they’re suitable themes for any Burton film.

Expressionism explores these themes through the construction of a dreamlike reality through unrealistic set design, lighting, and character. The primary purpose is to use sets, lighting, and character to show the inner psychology of the characters, and also elicit psychological tension in the viewer.

Set Design

Sets in German Expressionist films are typically theatrical, with crooked designs. Often the landscapes and backdrops are exaggerated and have high color contrasts. The sets often have jagged edges, while other parts are rounded, or tilted. The combination produces visually distorted and discombobulated spaces. This description fits the set design of the first German Expressionist film, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920). But it could easily describe the interiors of the haunted house in Burton’s Beetlejuice, or Batman’s Gotham City, though much of the kudos for Gotham goes to Burton’s spiritual twin: production designer Anton Furst.

Lighting

The use of lighting, specifically, stark shadows and silhouettes, intensify uneasy feelings of dread in German Expressionist cinema. Not only do the sets cast stark shadows, but so do the characters. The scene where the vampire’s shadow is cast against the wall in the film Nosferatu is an indelible image from German Expressionist cinema, which is often misidentified as Gothic in origin. Burton frequently referenced the image in films like Vincent and in Batman Returns, when The Penguin’s shadow is cast against the sewer wall.

Anthropomorphism

Burton’s films also borrow the Expressionist idea of anthropomorphism, or imbuing objects and animals with human-like qualities and actions. In Vincent, a creepy Jack-in-the-Box comes to life. In A Nightmare Before Christmas, there are numerous creatures and objects with human-like characteristics and behaviors. And in Beetlejuice, statues come to life during a wedding scene.

Character and Exaggerated Acting

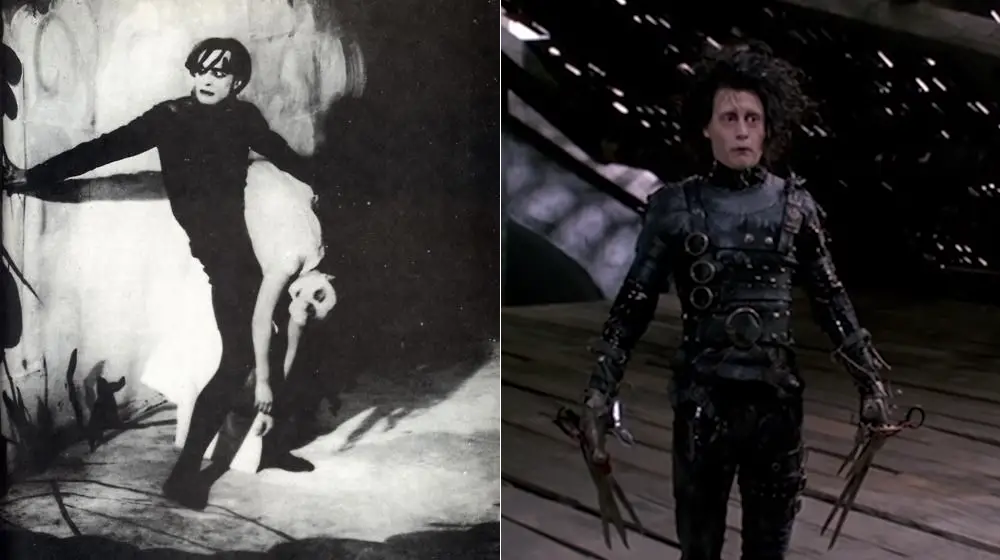

Many Burtonesque characters, like Edward Scissorhands and The Penguin, recall characters from German Expressionist films. Edward Scissorhands has the dark, elongated form of Cesare from The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920). Like Cesare, he is dressed head-to-toe in black and wears stark white makeup which contrasts with his black eye makeup. The Penguin has similar makeup too, while his look specifically recalls the creepy top hat-wearing Dr. Caligari.

This ghoulish effect is seen in many of Burton’s characters such as Willy Wonka, Betelgeuse in Beetlejuice, Barnabas Collins in Dark Shadows, Christopher Walken’s Max Shreck, and even in the elongated skintight costume-wearing Catwoman in Batman Returns.

The combination of distorted sets/props, lighting effects, and exaggerated character serves to place the audience inside the mind of an insane character in German Expressionism. An idea that Burton embraced.

The influence of German Expressionism is a ubiquitous presence across his diverse body of work from his two Batman films to Edward Scissorhands, Sweeney Todd, Dark Shadows, and Sleepy Hollow, to name only a few. As such, the art movement is the foundation of the Burtonesque visual style.

However, while a Burton film borrows visual tenets from German Expressionism, this does not mean the director adheres strictly to them. Burton is clearly well-versed in the darker visual arts, and his Burtonesque style is largely the intersection point of a number of different art movements.

The Gothic

Often, German Expressionism is mistaken for the Gothic, and that’s because German Expressionism influenced Gothic cinema. But German Expressionism and Gothic cinema also have their origins in the visual conventions established first by Gothic architecture, which were then appropriated for Gothic art of the Middle Ages, and finally by Gothic literature that began with Horace Walpole’s The House of Otranto.

All visual conventions that define Gothic architecture, art, literature, and cinema are pervasive across Burton’s filmography.

Gothic architecture, which originated in medieval Europe, centered on Gothic cathedrals, which displayed the three characteristics that define Gothic architecture: the pointed arch, the rib vault, and the flying buttress.

These visual characteristics can be seen in Burton’s Gotham City, but he never adheres to the Gothic. Instead, Burton gives an overall impression of the Gothic more than actually using it. His Gotham City conjures up the overall Gothic effect, through a mishmash of disparate architectural styles ranging from the work of Japanese architect Shin Takamatsu to the New York brownstone. Even Gotham Cathedral is not really Gothic. It’s Barcelona’s Sagrada Familia stretched and reshaped into something of a “broad stroke” Gothic structure, with Hitchcock’s House on the Hill from Psycho tacked on top.

This is fine because, like Gothic architecture, Gotham City is meant to induce an overall feeling of awe and dread.

This feeling of disquiet, became a central focus of the Gothic, and, as such, translated from the visual arts into literature. Horace Walpole, often viewed as the progenitor of Gothic literature, coined the phrase “Gothic story” with his novel, The Castle of Otranto (1764). His story established familiar tropes found in almost all stories in the Gothic genre: dark, ominous buildings surround by mist; tragic heroes and antiheroes; and a rapacious interest in the grotesque, weird, and grim proceedings. A century and a half later, these elements found their way into cinema.

However, Burton often turns the Gothic on its head. Rather than something to be shunned, and be frightened of (though his films feature that too), characters like Edward Scissorhands and Betelgeuse actually bring a certain charm to the Gothic. Beetlejuice, is a classic haunted house tale, rejigged for comedy, and a modern audience. And the costume, makeup, and hairstyle of Edward Scissorhands is more 80s Goth punk-rocker than Frankenstein’s monster. Burton’s Gothic tendencies continue throughout his work in films like Sleepy Hollow, Dark Shadows, Sweeney Todd, and even imagery in his Disney films Alice in Wonderland and Dumbo.

Memento Mori and Day of the Dead

It’s no secret that Burton is fascinated with death, and there is no shortage of cultural traditions, and art movements that explore it. Memento mori (Latin for ‘Remember You Must Die’) are symbols of the inevitability of death found in art and literature. The idea originated in ancient Rome, and became pervasive in art and theater in Europe. Typically symbolized by a skull (and often a complete skeleton) found in paintings, the influence of memento mori is found in a number of Burto films, especially the image of the Headless Horseman’s skull in Sleepy Hollow.

Similar images can be found in the Mexican festival, Day of the Dead, and the calaveras (colorful reanimated skulls and skeletons) and skull masks that parade streets at this festive time. Both Jack Skellington from The Nightmare Before Christmas, and the titular Corpse Bride allude to the walking calaveras.

However, while Burton references both the memento mori and the calaveras from The Day of the Dead, he might have been more directly influenced by famous stop motion pioneer, Ray Harryhausen, and his fighting skeletons in Jason and the Argonauts (1963). Burton is a noted fan of the film and Harryhausen, even labeling the make of the piano in Corpse Bride after him.

The Grand Guignol

A less known influence is the Grand Guignol, a theater in Paris which produced bloody stage plays. At a time when public executions were a form of entertainment, French audiences flocked to the Grand Guignol in droves to enjoy its realistic portrayal of sadism, rape, mutilation, and violent ends.

The theater influenced Burton’s musical, Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street, which, itself, is based on a play performed in London’s West End. Burton stages the film like a play, and doesn’t shy away from the violence when Todd cuts the jugular of his victims. Still, the violence is not quite on par with the Grand Guignol, where actors had their eyes put out, limbs sawn off, were frequently blown into pieces, and subjected to gruesome medical experiments, all in the name of a good night out. It was some of the most realistic special effects at the time. Actress Paula Maxa, the original Scream Queen, was killed and assaulted no less than 1,000 times in her career. Audiences either relished the violence, fainted, or ran from the theater in horror, only to return the following week.

Despite the gore, Burton borrowed another aspect of the Grand Guignol aesthetic for Sweeney Todd. Blood red dominated the macabre black and white shadowy backgrounds of sets and posters in Grand Guignol. As such, the combination of black, white and red is a deliberate choice by Burton in Sweeney Todd.

In other films, Burton retained some of the theatrics and insanity of the Grand Guignol, but with only the suggestion that something horrific could, or is about to, take place. Surprisngly, Burton successfully incorporated this trope into his work for Disney. Grand Guignol for children as it were. For instance, Burton made Willy Wonka’s Chocolate Factory like one big torture chamber, which is far removed from Gene Wilder’s kid-friendly film, Willy Wonka And The Chocolate Factory (1971).

Universal Monster Movies, Hammer Horror and 1950s Science Fiction

Burton spent his childhood in Burbank watching Hammer Horror Films, Universal Monster movies, and mid-century schlock sci-fi films. Directors like James Whale and Roger Corman, and actors like Vincent Price, Christopher Lee, and Peter Cushing were all childhood heroes. While Price and Lee later featured in Burton’s films, the striking imagery from Hammer, Universal, and Roger Corman directly influenced his visual style.

For instance, Burton devised a windmill for Sleepy Hollow which is very similar to the one burned to the ground in Whale’s Frankenstein (1931). He also uses low lying blanket of fog, a familiar trope in Hammer Horror, for one atmospheric scene.

Sleepy Hollow is Burton’s most direct homage to these old films. However, in most cases, imagery and tropes from these old horror and B-grade sci-fi movies served only as a starting point for Burton to create his own unique characters. Frankenstein’s monster from Whale’s masterpiece became Edward Scissorhands, and the Martians, which are such a ubiquitous presence in mid-century sci-fi, influenced the more sophisticated and comically scary aliens in Burton’s Mars Attacks! His Martians definitely channeled some of Roger Corman’s ridiculous-looking monsters and aliens. Burton also shares Corman’s delight in the zany combination of horror and humor, which pervade all of Burton’s work.

Freaks, Creepy Carnivals And Circus Performers

Closely related to the Monster movie and the B-Grade 1950s sci-fi flicks are the creepy carnival oddities. A long tradition of sideshow marvels and circus performers spanned Europe for centuries. The Wolfman (a man who’s face was covered in hair), midgets, and conjoined twins are just some examples of poor unfortunates, who were paraded as freaks of nature in these sideshows. As vile as these acts may be today, Burton has made them a recurring motif in his work, either directly referencing sideshows like he did with The Penguin’s past as the “Bird Boy” in Batman Returns, or by showcasing characters with deformities in general.

He shows empathy for many of these characters. Edward Scissorhands, who is an amalgamation of Frankenstein’s monster and Pinocchio, comes to accept his uniqueness over the curse of the film. Other characters, like Betelgeuse, completely accept themselves from the beginning, and take gleeful pride in terrorizing others. Betelgeuse is not strictly a villain. In fact, he helps to eradicate undesirable tenants from the house in Beetlejuice.

Burton, of course, has also crafted great villains with deformities. Burton. might sympathize with the misunderstood monster, but he’s also aware that some of these characters are just plain monsters in every respect. Deformities, in this case, enhance the villain’s infamy. Sometimes, the infliction of a deforming injury represents the character’s complete transformation into a villain. In Batman, Jack Nicholson’s Jack Napier becomes the deformed Joker after being dropped into a vat of acid. In the sequel, Batman Returns, Burton doubles down on the circus freak motif with his Penguin. The former “Bird Boy” who featured in circus acts as a child, is a hideous deformity who spits ink, and has malformed flippers for hands.

Associations with the creepy carnival didn’t stop there. The Penguin’s gruesome entourage are all former sideshow acts or circus performers. And Burton uses them to play into children’s fear of clowns. His henchman, Organ Grinder (Vincent Schiavelli) entices Gotham City’s first born into a creepy, life-size toy train, following The Penguin’s plan to send them all to their death. The idea of turning carnival fairgrounds into the top part of a villain’s lair, or over-sized toys into a villain’s vehicle, like The Penguin’s motorized, amphibious Rubber Ducky, is purely Burton.

The Bright And Dark Co-exist in Burton’s Color Scheme

This intersection of culture’s great art, theater, cinematic movements, and carnival acts concerning the dead and the grotesque resulted in a full spectrum of color that is uniquely Burtonsque. Bright colors are not expected in Gothic tales, but the dark, greyscale palette of this world is often juxtaposed against a goofy, almost candy-colored world of pastels, stripes and swirls. The Joker in his purples, greens, and orange is at odds with Anton Furst’s Gotham City, as is the creepy, hilltop Gothic mansion over-looking the pastel-colored suburbia in Edward Scissorhands.

These bright colors can be found in a number of traditions absorbed into the Burtonesque visual style including the Day of the Dead and the bright color schemes of the circus and carnivals. The Gothic and gore often take place in bright, sunny, and oversaturated settings. The Gothic couple in Sweeney Todd taking a leisurely stroll on the pier on a cloudless day, the zany and colorful horror-house factory in Charlie And The Chocolate Factory, or the landscapes of Wonderland in both Alice films, are all examples of this uniquely Burtonesque trait. In these worlds, colors are often bright, but the deeds are dark.

Burtonesque Is Eclectic

Burton’s eclectic style works. His isolated childhood spent absorbing all these images from film, and art, and his time spent drawing and making films in his hometown helped develop a unique point of view. The deconstruction of his visual style shows that even a unique vision is grounded in well established traditions.

Tim Burton’s films stand out on their own. Knowing the influences behind his work gives us a better appreciation for everything he creates, and the kind of person he is. If Burton had not suffered an isolated childhood, and felt disconnected from those around him, Beetlejuice, Batman, or Edward Scissorhands would not exist. Like his characters, Burton has come to accept his unique vision and unique view of the world. For Burton, the hum drum reality of suburbia is the nightmare not the haunted house. That is where the fun is.