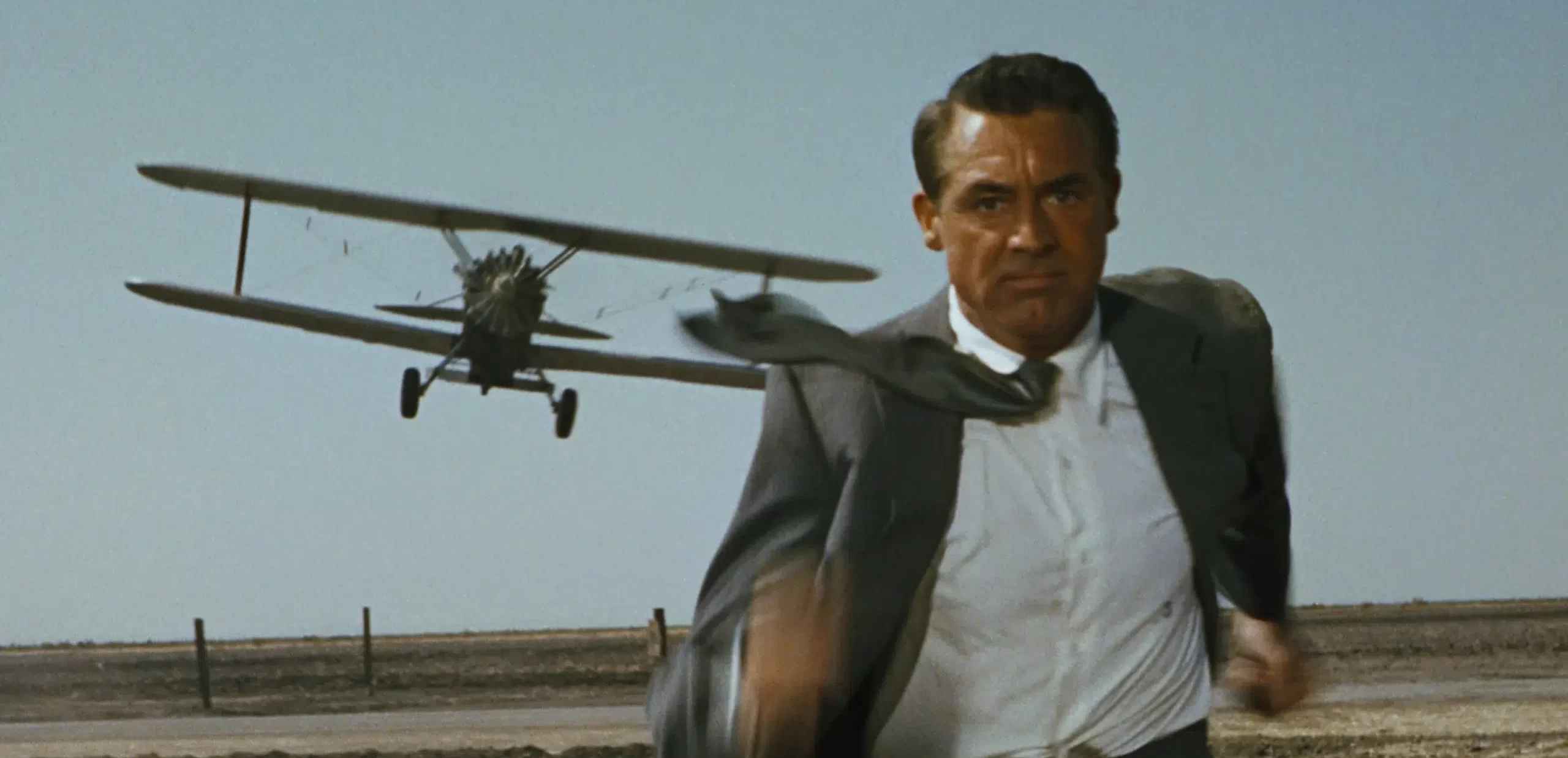

The helicopter attack in From Russia With Love is often unfairly dismissed as a rip-off of the celebrated crop-duster chase in Alfred Hitchcock’s North By Northwest.

While the continual attempts made by the low-flying helicopter to clip James Bond (Sean Connery) mirrors the attacks of the dive-bombing bi-plane on Roger Thornhill (Cary Grant) in Hitchcock’s classic 1957 spy film, the purpose of the two chase sequences couldn’t be more different.

As we’ll see, the approach to scripting, shooting, and editing both action sequences is determined by the two very different personalities of each film’s protagonists. Even the build-up to the two sequences is different.

In addition, there are innovations in editing, special effects, and location shooting that makes the helicopter attack in From Russia With Love deserve reappraisal in its contribution to the Bond series, and action filmmaking in general.

Hitchcock pioneered the idea of an aircraft chasing a man on foot. The sight of Cary Grant in a suit running from an aircraft in the middle of nowhere is so iconic that almost everyone knows the image without seeing the film.

The sequence occurs an hour into the film. Thornhill is lured into the middle of nowhere to hopefully learn why he’s been mistaken for George Kaplan, a man that his assailants want dead. Instead, he’s been lured there to die.

He desperately searches for a way out of the situation, briefly taking refuge in a cornfield. But the crop duster does what crop dusters do, and sprays the cornfield with fertilizer to flush Thornhill out.

Thornhill’s only chance is to wave down a passing truck. After the truck screeches to a halt and nearly runs Thornhill down, the pilot misjudges his final swoop and crashes into the truck’s tanker.

Thornhill is out of his depth. He’s fearful for his life and survives only because of luck.

Bond, on the other hand, turns the table on his assailants.

The villains are desperate in From Russia With Love’s helicopter sequence. For most of the film, SPECTRE has been one step ahead of 007. But when their agent, Donovan “Red” Grant, fails to assassinate Bond and steal the Lektor, a Russian decoding machine they carefully orchestrate Bond to steal from a Russian Embassy, SPECTRE is now on the back foot.

Bond has turned the tables on SPECTRE, and now we see a change in the criminal organization’s attitude.

Desperate to kill Bond before he returns to MI6 with the Lektor, SPECTRE sends a helicopter to intercept.

Unlike Thornhill, Bond is not lured anywhere. SPECTRE is trailing him. He soon takes control of the situation and lures the helicopter into a position where he can dispatch of it and its pilots.

Using the Lektor, Bond lures the SPECTRE helicopter away from a truck to protect Bond Girl Tatiana Romanova (Daniella Bianchi). He effectively uses himself as bait, deliberately, while Thornhill is the unwitting quarry from the beginning of the crop-duster sequence to its end.

The helicopter makes desperate swoops, narrowly missing 007. Bond ducks and dives out of the way, until he finally takes refuge underneath a rocky outcrop. The helicopter hovers overhead. As the SPECTRE co-pilot prepares to drop a hand grenade on Bond, the British agent quickly assembles his rifle and shoots the co-pilot in the shoulder. Wounded, the SPECTRE agent drops the grenade inside the cockpit. Moments later, the helicopter explodes and the burning wreckage falls meters away from Bond.

Bond casually returns to the truck, and holds Tatiana in his arms as the wreckage explodes behind them, as he quips: “I think one of their aircraft is missing.” A classic Bond sequence.

So we’ve seen similar elements used in both North By Northwest’s Crop Duster sequence and From Russia With Love‘s helicopter attack:

- a remote location

- a dive-bombing aircraft pursuing a man on foot

- a temporary place to take refuge (the cornfield and the rocky outcrop)

- and a fiery demise to the aircraft.

Director Terence Young deliberately chooses different aircraft, locations, and weapons to differentiate the helicopter attack from the crop-duster sequence, including:

- a helicopter instead of a crop-duster bi-plane

- hand grenades instead of a machine gun

- a rocky outcrop instead of a cornfield

- a hilly, green, cold location instead of a desolate, brown, flat, scorching hot rural location

That alone would be a rip-off, but so much more differentiates the two sequences.

Each Sequence Highlights Different Character Traits of its Main Character

Young used the similar idea of the swooping aircraft from North By Northwest to showcase completely different character traits and motives in 007.

James Bond could not be more different than Roger Thornhill.

Bond is in control of the situation. Thornhill is out of his depth.

Bond protects Tatiana. Thornhill tries to protect himself.

The helicopter attack leads Bond one step closer to success. Thornhill’s predicament becomes even more mystifying.

Bond deliberately turns the tables on his assailants and destroys them with skill. Thornhill escapes by sheer luck. He never gains the upper hand in the crop duster sequence. It is just a matter of luck that he dodges the in-coming plane and it ends up crashing into a tanker and exploding.

Thornhill is just a regular guy caught up unexpectedly in a spy caper.

Bond is a veteran agent and the best at his job. He’s expected to find the advantage and come out on top.

So, while the helicopter sequence is a homage to Hitchcock’s most famous sequence, director Terence Young makes the helicopter sequence in From Russia With Love its own and simultaneously establishes the basic recipe that most Bond action sequences will follow.

The First True Bondian Action Sequence

What we’re seeing in the helicopter sequence is the beginning of the classic cinematic Bond payoff: Bond, who is on the back foot, gets the upper hand in the final moments. Bond outwits his assailant that in turn gives the audience that ‘Yes’ moment that is so crucial in a satisfactory payoff to any Bondian action sequence. Here, Bond uses his rifle to shoot the co-piot in the arm, who then drops the hand grenade inside the cockpit with the helicopter exploding moments later. Bond has used their own weapons to destroy them. This concept becomes commonplace in Bond action set pieces to follow. (Later, some Bond action sequences will substitute this element with Bond making a miraculous escape, which is first showcased in his jetpack escape in Thunderball.)

Following the adversary’s demise, Bond delivers a quip which helps resolve the tension of the sequence.

Elements of this can be seen in the car chase in Dr No in which Bond makes a quip while looking at the burning wreckage of his assailant at the bottom of a slope and certainly Bond uses Red Grant’s watch and its retractable garotte wire against him in From Russia With Love‘s train fight. But there’s no humour in the latter.

Every element is put together in From Russia With Love‘s helicopter attack:

- Bond on the back foot turning the tables on his adversary

- Bond using a quip to release tension and end the action on a humorous moment

And another element we’re yet to talk about:

- Bond beating a more formidable adversary with a gadget given to him earlier: in this case his disassembled rifle.

Bond uses his rifle and his position under the rocky outcrop to gain the upperhand.

Young used a device called Chekov’s Gun, quite literally. Simply put, Bond received a rifle in the briefing scene earlier in the film and so he must use it at some stage in the story. According to playwright, Anton Chekov, everything has to have a purpose in a story. So if you show the character with a gun, that character has to use that gun, otherwise the audience feels cheated.

It can be any object. It doesn’t have to be a gun. For example, in the next Bond film Goldfinger, gadget-master Q demonstrates the gadgets on the Aston Martin DB5 to Bond. According to Chekov, Bond must now use all these gadgets in the film. It’s expected, and indeed this Q briefing scene becomes a familiar trope in almost every Bond film to follow. But it was first developed in From Russia With Love when Q shows Bond his attache case and rifle which Bond uses to great effect in the train fight and the helicopter attack respectively.

With all these elements, the helicopter sequence is the first true Bondian action sequence. There were action sequences beforehand but this one establishes the format and style that is used over and over again in future Bond films.

Young is concerned with action. Hitchcock is more concerned with suspense

The success of North By Northwest’s crop duster sequence is largely due to the six-minute suspenseful buildup that occurs just prior to Thornhill being attacked by the plane.

Thornhill is dropped off by bus on a desolate roadside in the middle of nowhere. The whole sequence is set up to subvert a tired thriller trope: the man lured to an inner-city street corner on a cold, rainy night only to be gunned down by an unseen passerby in a black car.

Hitchcock builds the suspense by having car after car pass, but each turn out to be no threat at all. Then a man appears on the other side of the road, and Thornhill approaches him wondering if he is the man he is meant to meet. He turns out to be a local waiting for a bus. But as he gets on the bus the local man comments on the distant plane dusting crops where there are no crops.

That one line of dialogue identifies the plane as the threat.

This careful buildup of suspense punctuated by the sudden realization that the plane is the threat makes the following crop duster chase more impactful.

By contrast, there is absolutely no suspenseful buildup to the helicopter attack in From Russia With Love.

The helicopter appears over the truck Bond is driving, and the action sequence begins immediately with the co-pilot of the SPECTRE helicopter strafing Bond’s truck with grenades. The helicopter attack sequence’s primary purpose is action, with a few suspenseful moments added for effect like the tense moment in which Bond must assemble his rifle and shoot the co-pilot before the SPECTRE operative drops a hand grenade on him.

Both sequences use suspense and action, but each sequence favors one over the other.

We can also see this in each director’s deliberate choice to either show or not show the pilots. Hitchcock wants the pilot to remain unseen in the crop duster sequence in North By Northwest because it makes the bi-plane a more ominous threat thereby elevating suspense, while seeing the two helicopter pilots and their point of view are necessary for the helicopter sequence’s action, especially the climax.

We need to see the co-pilot in order for the climax to work when Bond shoots him in the shoulder and he drops the grenade inside the cockpit.

Different Cinematography, Different Approaches to Filming

The cinematography is also different. Terence Young does not try to emulate the lighting, framing, composition, or camera angles of the crop-duster sequence in North By Northwest.

North By Northwest’s Carefully Framed Shots

In the crop-duster sequence, each shot was framed precisely to what Hitchcock wanted.

Each shot was part of a detailed shot list, which Hitchcock first perfected. He even acted out each shot in the living room of Ernest Lehman, the screenwriter of North By Northwest.

Lehman then wrote most of these camera angles in his script which mostly conforms to the shots and camera angles in the final filmed sequence.

Cinematographer Robert Burks drew up each shot and camera angle in a diagram which he used to film the crop-duster sequence on location.

Hitchcock needed this precision to perfectly build up the suspense of the sequence.

The shooting script shows Hitchcock included shots from the pilot’s POV, but this was later scrapped, which made the attack from the crop duster more ominous.

The whole sequence is from Thornhill’s point of view. The audience feels his confusion, his anxiety, and his terror. Lured into a trap, there seems to be no way out except for his brief refuge in a crop before the crop duster sprays it with fertilizer to flush him back into the open.

Every shot is perfectly composed and edited together. There’s a symmetry to those wide swoops of the plane and certainly Hitchcock would never dream of “crossing the line.”

The Documentary-Style Shaky Footage of The Helicopter Attack

By contrast, the helicopter attack in From Russia With Love was never storyboarded, nor was a shot list firmly tied down before shooting began.

The sequence has a documentary feel with its imperfectly composed shots and is one of the first examples of shaky cam footage.

Some reviewers at the time, like Robin Wood, chastised the sequence for “crossing the line” during the action. Indeed, the helicopter often comes from every direction. But was this deliberate?

Young’s intention is to immerse the viewer in the sequence. This immersion wasn’t achieved through point-of-view shots like the crop-duster sequence, but through filming techniques that allowed the audience to experience the chaos of that attack.

It’s deliberately chaotic and messy to increase anxiety and excitement in the viewer. This documentary-style approach to filmmaking is certainly novel for the time, as is Peter Hunt’s frenetic editing style. Both are a precursor to the hand-held shaky camerawork of director Paul Greengrass in The Bourne Supremacy and The Bourne Ultimatum.

More footage was shot than needed and then the best shots were edited together by Hunt.

Most of the helicopter attack was shot on location, with only one rear projection shot and the destruction of Bert Luxford’s helicopter miniature on a soundstage at Pinewood Studios.

North By Northwest’s crop duster sequence is also mostly shot on location. However, there are far more rear-projection shots of the plane dive-bombing Cary Grant, which are inserted rather seamlessly in the sequence. The sequence also ends with the fiery explosion of a miniature, this time two: the bi-plane and the tanker.

There is no doubt about the influence Hitchcock had on the Bond series as a whole, especially on From Russia With Love, but the helicopter attack should be viewed as just as innovative in its own right, especially on modern action filmmaking and editing.