In the vast archive of unmade cinema, most “lost” films are merely fragments—a pitch on a napkin or a half-finished outline. But Forever and a Death is different. It is a complete, high-octane thriller written by a Grand Master of crime fiction that was fully intended to be the 18th James Bond adventure.

It was killed not because it was bad, but because it was too dangerous.

This is the factual history of Donald E. Westlake’s rejected 007 screenplay, how it terrified the studio, and how it eventually survived by shedding the name “James Bond.”

The Assignment (1995)

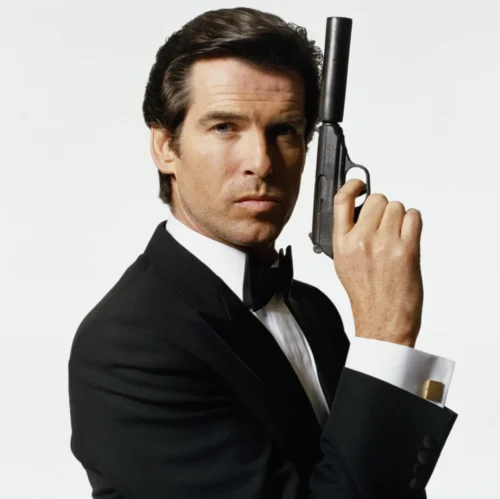

Following the massive success of GoldenEye in 1995, EON Productions found themselves in a difficult position. They had successfully rebooted Bond for the post-Cold War era, but they needed a story for the follow-up that could match the grit and modernity of Pierce Brosnan’s debut. To achieve this, Producers Michael G. Wilson and Barbara Broccoli turned to Donald E. Westlake.

Westlake was not a typical blockbuster screenwriter; he was a novelist, famous for the ruthless Parker series. Hiring him was a clear signal that EON wanted a script with hardboiled intelligence, complex plotting, and a darker edge than the franchise’s usual fare.

The Plot: Revenge, Ruin, and Gold

Westlake built his script around the most significant geopolitical event of the late 1990s: the Handover of Hong Kong. On July 1, 1997, the United Kingdom was scheduled to return sovereignty of Hong Kong to China.

The villain, Richard Curtis, is a formerly wealthy British businessman thrown out of Hong Kong during the transition. Facing financial ruin and consumed by a desire for revenge, Curtis devises a dual-purpose plan:

-

The Heist: Tunnel under Hong Kong’s bank vaults to steal their gold reserves.

-

The Cover-Up: Trigger a man-made natural disaster to destroy the city and hide the theft.

The Goldfinger Connection (Novel vs. Film)

In the published novel, Curtis’s plan functions as a fascinating hybrid of the two versions of Goldfinger:

-

Like the Novel: It involves a physical heist to steal bullion.

-

Like the Film: It uses a weapon of mass destruction. But instead of irradiating the gold, which is the movie villain’s plan, Curtis plans to use a weapon of mass destruction to cover his theft.

A Key Mystery: It remains unclear if the elaborate gold heist was part of the original screenplay or an addition Westlake made for the book. In the afterword of the 2017 edition of the novel, Jeff Kleeman, a former United Artists production executive, describes the villain’s motivation purely as “scorched earth” politics. It is highly possible Westlake added the “bank job” element later to play to his strengths as a master of the caper genre.

The Weapon: The “Soliton” Wave

For the threat, Westlake eschewed space lasers for terrifyingly plausible science. He researched Solitons—self-reinforcing solitary waves that maintain their speed and shape over long distances.

Curtis plans to detonate a device underwater to send a Soliton wave through the water table beneath Hong Kong. This would trigger soil liquefaction, turning the reclaimed land beneath the skyscrapers into sludge and causing the city to slide into the harbor. It was a heist disguised as a geological event.

The Afterword: Why the Movie Was Banned

Kleeman explained exactly why the film was never made.

The “Un-Building” Logic

Kleeman confirms that Westlake’s pitch for the villain was grounded in a twisted sense of ownership. The villain viewed the Handover not as a treaty, but as a theft. His logic was stark: “I built this. If they take it from me, I will un-build it”.

The Political Risk

As the July 1, 1997 date approached, the studio realized the danger. Releasing a blockbuster where a Westerner destroys Hong Kong during the actual handover was a diplomatic nightmare. They feared it would cause an international incident or get the film banned in Asian markets.

The Tone Clash

Additionally, the studio felt Westlake’s script was too intellectual. It focused on the “how” of the engineering and the process, lacking the “popcorn” energy audiences expected from a summer movie. The script was scrapped, and the team pivoted to the media-mogul plot of Tomorrow Never Dies.

The Resurrection: The Bond That Never Was

Westlake knew he had a great story. Years later, he “reverse engineered” the script, stripping out the Bond IP.

-

George Manville (The Bond Role): A rugged engineer who helped design the Soliton technology. In the book, he isn’t a spy, but a competent professional forced into heroism—much like Westlake’s other famous protagonist, Parker.

-

Kim Baldur (The Bond Girl Role): An environmental activist and diver for “Planetwatch.” She is the one who discovers the underwater testing, serving as the moral compass of the story.

-

Barrett (The M Role): An older, wiser engineer and mentor figure who provides Manville with the intelligence and support needed to track Curtis.

Westlake died in 2008, but the manuscript was discovered and published by Hard Case Crime in 2017 under the title Forever and a Death.