Written and performed by Argentinian composer Lalo Schifrin, the jazzy, bongo-driven instrumental known as “Burning Fuse” is instantly recognizable as the theme to the hit tv series Mission: Impossible (1966-73). As far as spy music goes, the James Bond theme by Monty Norman might be the gold standard, but Schifrin’s theme is no less catchy, and frequently ranks as one of the ten most well-known themes of all time. Schifrin originally wrote a different theme, but the series creator, Bruce Geller didn’t like it. Instead, Schifrin was told to use music he wrote for an action sequence in the show’s first episode as the show’s main theme. Schifrin wisely changed the composition, but it was no less memorable.

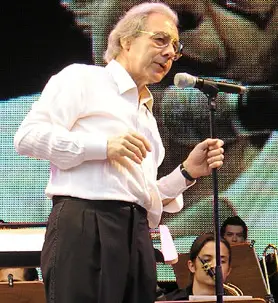

In the video below, Schifrin explains how he came to work with Geller and write the theme.

As Schifrin explained, he did not have much to work with. When he first met Geller, he watched actors Martin Landau, Steven Hill, and Barbara Bain in action during the filming of the pilot at Desilu Studios in Culver City, California. But it didn’t help. “I did not understand anything, because I had never been to a TV shoot,” Schifrin told Soundtrackfest. “Everything was very slow, and everything went in different order. Without the script, when one of the characters said something, I did not understand anything. Bruce [Geller] didn’t have time to ask me for anything specific with the music.”

Schrifin also had no main titles, which help in the composition of a suitable theme. Geller just told him that each episode would likely begin with a match lighting a fuse. With the vague call for a theme that fit the “paramilitary” nature of the Impossible Mission Force (IMF), Schifrin composed “The Plot”, based on martial music. Geller liked it, but wanted “something exciting.” He let Schifrin watch a rough cut of the pilot. Now edited into a proper narrative, the exciting plot featuring IMF’s search for two missing nuclear warheads taken to a Caribbean island helped him formulate a suitable composition.

The spy organization’s objective–to find two nuclear bombs–is very similar to the plot of a James Bond film. But the way IMF resolves the situation as a team, through elaborate deception, diverged from the Bond films reliance on spectacle. As such, Schifrin’s final theme used similar instruments to the James Bond musical score, but arranged differently. Both feature the combination of a fender guitar and fender amp (complete with jangly reverb and vibrato) that was so popular in the early 1960s, but the key difference with Schifrin’s theme is the time.

The time signature (also known as meter signature or measure signature) is a notational convention that specializes how many beats (pulses) are contained in each measure, and which note is equivalent to a beat.

Schifrin’s Mission: Impossible theme is in five-four time. Most pieces are in an even number like two-four or four-four, or maybe three-four in waltz time. But five-four is a very unusual signature. Even the Mission: Impossible movie series starring Tom Cruise performs the theme in four-four time because it is easier to perform. But no matter how much the modern rearrangement is enhanced with a techno or rock arrangement, it just doesn’t hold a candle to Schifrin’s original instrumental piece.

Schifrin’s Mission: Impossible theme is similar to the five-four time of Dave Brubeck’s Take Five. Have a listen, and see if you can pick out that five-four time in Brubeck’s great jazzy classic.

“I suppose the Dave Brubeck Quartet’s ‘Take Five’ was in my heart, but the 5/4 tempo just came naturally. It’s forceful, and the listener never feels comfortable,“ Schifrin told The Wall Street Journal. Of course, Schifrin uses five-four time to create something entirely unique, but that five-four time is the foundation of the score.

Shifrin uses an off-kilter 5/4 time with a sharp percussive blast of bass and woodwind. It gives the music that intrepid sound of an agent giving chase, or thwarting some nuclear countdown. Without a doubt, Schifrin’s music was instrumental in turning Mission: Impossible into a hit. And it is also what got Tom Cruise interested in turning the tv series into a blockbuster movie franchise.

“When Tom Cruise saw me,” Lalo Schifrin said in an interview with a Montreal radio station, “…he said he grew up with the television series and the music was one of the biggest elements that convinced him to get involved in the movie project, not only as an actor but as the co-producer.”

The Mission: Impossible films use the basic theme, but as stated before, they’re in 4/4 time, not Schifrin’s 5/4 time. Famous composer John Williams was originally hired to compose the theme for 1996’s Mission: Impossible, but he wanted to compose something original. Director Brian De Palma didn’t agree, and hired Batman composer Danny Elfman instead. In addition, U2’s Adam Clayton and Larry Mullen produced a techno makeover which ranked at number 7 on the Hot 100.

Cruise, who is the producer of the series, made the decision to hire distinct and original composers for each successive instalment. For the sequel, Hans Zimmer composed a rock arrangement of the theme, and Limp Bizkit incorporated the theme into their nu metal-inspired track entitled “Take a Look Around.”

The next four films brought into three different composers. But it was composer Joe Kraemer and Rogue Nation director Christopher McQuarrie, especially, who decided to ground the theme in Schifrin’s original score.

McQuarrie told NPR: “For Joe and I, it was a very simple course of saying…”Let’s really embrace the theme, and let’s embrace the theme going all the way back to the TV show.”

They made the decision to go back to five-four time, by breaking it down “measure by measure, and recognized fully that there were elements of it that are campy,” McQuarrie explained. “We had such a shorthand, and had compartmentalized the different beats of the theme song, so that we could avoid ever becoming too heightened.”

Schifrin finally received an Oscar for this score on 18 November, 2018, when the board of governors of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences recognized his work.