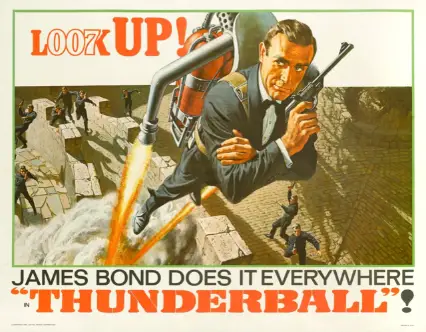

Bell-Textron Rocket Belt: James Bond’s Jetpack Never Quite Took Off For Military Use But Inspired The Ones That Will

In May 1964, Bill Suitor was about to become famous. Soon he’d make a legendary flight in a real-life jetpack for the latest James Bond film Thunderball.

At 19-years-old, Suitor had come a long way in a short time. Wendell Moore, the inventor of the Bell-Textron Rocket Belt, had spotted Suitor mowing lawns next door and offered him the job as the jetpack’s test pilot. The unusual request was to prove one thing: that anyone could fly it. Since 1955, Moore, who worked for Bell Aerodynamics, had developed the rocket belt for U.S. infantrymen on the battlefield. The sale to the U.S. Army depended on ease of use, among other things.

Unfortunately, the Bell-Textron Rocket Belt was far from easy to fly. Suitor was a natural. He had mastered flying the device in a few short months but even he later described learning to fly the Rocket Belt as like “trying to balance while standing on a beach ball on the ocean”. Now he was about to fly the jetpack as James Bond.

Suitor was one of only two people who could fly the Bell Textron Rocket Belt at the time. The other, Gordon Yaeger, would be grounded that day.

Both men were brought to Chateau d’Anet in northern France, where the pre-title sequence for Thunderball would be filmed.

007’s short flight in a jetpack would transform the Bond series in one significant way:

The jetpack flight was the first truly amazing stunt in the Bond series.

The jetpack stunt would also begin a Bond tradition. In subsequent pre-title sequences, Bond would often have to perform a death-defying stunt to get out of an impossible situation, reaching its high-point with the unmatched skiBASE jump in The Spy Who Loved Me.

Bond’s mission is to kill Jacques Bouvar, an agent of the Special Executive of Counter-intelligence, Terrorism, Revenge, and Extortion (S.P.E.C.T.R.E).

Bouvar has faked his own death, but Bond notices that the widow at the funeral is really Bouvar in drag. After punching him in the face and taking off his black veil to reveal the man underneath, the two engage in a brutal fight to the death. Bond wins of course. But soon, more agents pursue Bond onto the balcony of Bouvar’s chateau. It’s a dead end. But, with little time to spare, 007 makes a daring escape by jetpack over the chateau roof, landing close to his waiting Aston Martin DB 5.

Shots of Sean Connery donning a replica jetpack were spliced together with wide shots of Suitor flying the device. Suitor balked at the suggestion he should fly without a helmet. When he refused, his helmet was painted brown to match Connery’s hair. But it didn’t work and Connery donned a helmet for reshoots in front of the rear projection screen to match-up with the footage of Suitor.

The Bond films were the first series to bring futuristic technology into the present, back from the far-off future of science fiction. Previously jetpacks were in comic strips like Flash Gordon or Buck Rogers, or were faked with rickety old special effects found in old black and white movie serials that were little more than a dummy flying on wires.

Even though Bond’s flight looks rather slow today, in the mid-60s, the sight of a real jetpack defied imagination and just helped solidify the Bond series as the first blockbuster film series.

In reality, the Bell Textron Rocket Belt wasn’t a jetpack. It used rocket fuel not jets. More importantly, it was a flop.

The rocket belt could reach a height of 33 feet (10 meters), but only remain airborne for 21 seconds before using up its 5-gallon tank of fuel. The U.S. Army canceled rollout of the rocket belt due to dangers associated with its short flight time and the intense heat of its propulsion, not to mention how difficult the contraption was to use.

In Suitor’s book, Rocketbelt Pilot’s Manual: A Guide by the Bell Test Pilot, he jokes that a pilot was “going to have a bad day” if they were still 20 feet in the air after 20 seconds of flight time. Bell tried various ways to combat this problem, first by strapping an egg timer to a pilot’s wrist, which would start to go off at 20 seconds. But the pilot often didn’t hear the alarm causing a sudden drop in altitude. So a vibrating device was placed at the nape of a pilot’s neck, “which,” Suitor wrote, “would start pounding your skull to tell you to get down.”

The other problem—the intense heat–came from how the device turned its fuel—hydrogen peroxide—into superheated water vapor, which is what gave the device its propulsion.

The science behind it is simple enough, as Q might explain to a disinterested 007.

The rocket pack is comprised of three cylinders strapped to the pilot’s back. One is a gas cylinder filled with nitrogen gas, while the other two contain a 90% solution of highly concentrated hydrogen peroxide.

When activated, a valve opened in the nitrogen tank and pumped the hydrogen peroxide into a catalyst chamber, which consisted of fine silver or platinum meshes. The meshes act as a catalyst, rapidly decomposing the hydrogen peroxide and producing superheated water vapor, which is basically steam at a high temperature around 730°C (1,350°F).

The steam was forced out of two nozzles that were directed under the arms of the pilot.

The immediate vaporization of the hydrogen peroxide accounted for the short flight time as the fuel is expended rapidly.

And it was hot, very hot. The pilot needed protection from the intense heat by wearing a fiberglass shield.

Despite the dangers, Suitor would fly the contraption 1,200 times, including a high-profile flight for the opening ceremony of the 1984 Olympic Games. Certainly, its exposure in Thunderball helped the jetpack get the gig at the Olympics.

Jet Packs would be considered for future James Bond movies, first in Moonraker then in the pre-title sequence for The World Is Not Enough. Bond chasing a female terrorist down the Thames via jetpack would be replaced by the gadget-laden Q Boat in the final film.

But the Bell-Textron Rocket Belt is more than a prop trotted out for use in movies and at special events. The idea for using jetpacks for military use has refused to die. The U.S. Military who worried about the intense heat, short flight time and impractical learning curve of the device, felt that additional research into using jet engines, rather than steam, might extend flight time.

The result was the WR19, a small-scale turbo jet engine invented by Sam Williams. With a thrust of 1,900 newtons, the WR19 replaced the hydrogen-peroxide rocket, allowing Moore and Bell Aerodynamics to improve flight time from 21 seconds to 5 minutes.

Dubbed the ‘Jet Belt’, the pack was too heavy and there was a risk of spinal injury on landing. Within weeks of the first test flight, Wendell Moore died and research into jet packs stalled for the next few decades. The WR19 engine kept Bell profitable when it was adapted for the Tomahawk TLAM missile and other missile systems since the 1980s.

Around 2000, interest in jet packs took flight once again. Entrepreneurs—including a number of ex-military personnel—built on what Moore and Bell Aerodynamics discovered. The most significant designs thus far have been made by Jetpack Aviation and Gravity Industries.

Jetpack Aviation began in 2006, with its most recent iteration, JB12, which remains classified, but has six engines, three turbojet engines per side on a wearable frame like its predecessor JB11. The JB12 is 105 pounds, which is lighter than the JB11, and can hover and maneuver in any direction and reach a top speed of 120 mph.

While not yet available to the public, two JB12s have been sold to an undisclosed southeastern military, along with a speeder bike also developed by Jetpack Aviation.

But Jetpack Aviation does have one worthy competitor for medical and military use in Gravity Industries.

In 2022, paramedics with The Great North Air Ambulance Service (GNAAS) tested Gravity Industries jet suit in the Lake District of UK, showcasing some impressive footage (below) of the test flights.

The jet suit, developed by inventor Richard Browning from Gravity Industries, has a ten-minute flight time and can travel up to 85mph. The jet pack is seen as ideal for mountain rescues, and other previously inaccessible locations.

Last year, the British Royal Navy also began trialing jet suits from Gravity Industries with Royal Marines performing flying tests in the English Channel for future boarding situations. The footage (below) is impressive and could be a scene from a James Bond movie itself.

The marines took off from a rig fixed onto a small boat behind HMS Tamar and flew onto its deck, and dropped down a ladder so other marines could board. The Navy has also been testing the idea of Jet Suit Assault Teams since 2023. But the jet suit comes with a hefty price tag of £300,000 each.

Gravity Industries’ founder Richard Browning served in the British Royal Marines before becoming a jet pack entrepreneur. Soon, we might see James Bond donning a jetpack like Gravity Industries jet suit in a future James Bond film.