Little Nellie: The Making Of 007’s Aerial Battle In ‘You Only Live Twice’

Pilots and cameramen risked life and, especially, limb to film cinema’s first helicopter dogfight

In You Only Live Twice, James Bond took to the air in a Wallis WA-116 Agile autogyro, nicknamed Little Nellie, on a reconnaissance mission to find Blofeld’s volcano base.

The Wa-116 autogyro is an unusual and rickety contraption for a Bond film’s signature action sequence. However, while Bond’s small autogyro looked flimsy, she was packed with more armaments than a jet fighter and easily dispatched her much bigger assailants: four machine-gun-toting Kawasaki-Bell 47G-3 helicopters.

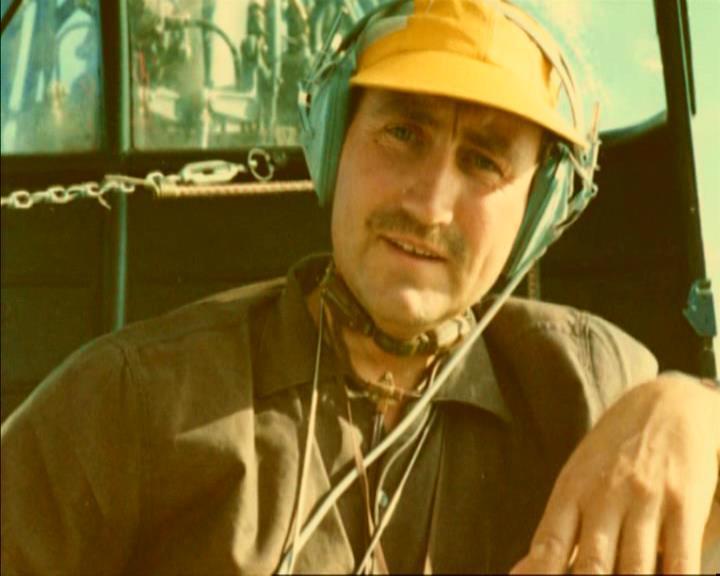

Retired RAF Wing Commander Ken Wallis designed the British autogyro in the early-1960s. Little Nellie got her name from a British tradition in World War Two that involved giving anyone with the name Wallis or Wallace the nickname of Nellie after the British singer and actress Nellie Wallace.

Wallis, a seasoned pilot who flew a Wellington bomber on 36 missions over Germany and Italy during WWII, was also a gifted engineer. His improvements on past autogyros included an offset gimbal rotor head which gave Little Nellie hands-off stability. With a two-stroke piston engine, the Wa-116 autogyro could reach a top speed of 130 mph and an acceleration of 0 to 96 in 12.5 seconds. The first prototype flew on 2 August 1961, and another five were built in 1962.

The British Army Air Corps showed interest in three of them, but Little Nellie would become famous after her debut as an unlikely vehicle for James Bond.

Little Nellie is part of the Bond producers’ long tradition of finding more unusual or exotic vehicles for Bond to pilot, from the cool (like the word’s smallest jet) to the bizarre (like a one-man submersible that looked exactly like a crocodile).

During pre-production on You Only Live Twice, production designer Ken Adam learned about the WA-116 autogyro while listening to the BBC Today radio show. The show’s host Tony Scase interviewed Wallis about the autogyro’s capabilities. Adam, a fighter pilot in World War Two, saw the autogyro’s potential immediately and called the BBC for Wallis’s phone details. Soon after the film’s aviation adviser Hamish Mahaddie rang Wallis, who eagerly agreed to fly his autogyro in You Only Live Twice.

On 14 June 1966, Wallis demonstrated the autogyro to producer Albert R “Cubby” Broccoli at Pinewood Studios in London. “When I landed Cubby Broccoli said, ‘Yes we shall want it in Japan in six weeks’ time,'” Wallis said in the documentary Inside You Only Live Twice.

Finding Blofeld’s volcano base and a suitable location for a helicopter dogfight

The idea for filming a helicopter dogfight in You Only Live Twice came from a three-week location recce in Japan weeks before Ken Adam had even heard of Little Nellie.

The purpose of the air reconnaissance was to find a Japanese castle situated on the coast, which Ian Fleming used as Ernst Stavro Blofeld’s lair in the novel You Only Live Twice. However, after spending seven hours a day over a three-week period searching two-thirds of Japan, the crew discovered the Japanese never built castles near the sea.

What they did find, however, was this extraordinary national park with twenty-one volcanoes, some of them active.

The “moonscape”, as Adam called it, left a lasting impression, and long-time Bond editor Peter Hunt noted its suitability as a backdrop for a helicopter chase.

The footage of a volcano also impressed Broccoli. He scrapped Fleming’s castle lair in favor of a hollowed-out volcano base, which, in the film, would house a space rocket that swallowed American and Soviet space capsules. Screenwriter Roald Dahl replaced a car chase in the script with the sequence in which Bond uses the autogyro to survey the area in search of Blofeld’s volcano base and is attacked by SPECTRE helicopters.

Designing and Installing the Gadgets

With the location, autogyro, and the idea for a helicopter dogfight selected, Ken Adam and special effects supervisor, John Stears, discussed which armaments should be installed into the autogyro.

Even though Dahl incorporated Little Nellie into the screenplay, the sequence was designed around the gadgets Adam and Stears selected (Storyboards of the sequence can be found here).

Adam also came up with a great introduction for Little Nellie. The autogyro would be assembled from four crocodile skin suitcases, which Adam’s wife, Letizia, designed. The real autogyro, itself, could not be de-assembled or re-assembled, so the crew made a non-functioning mock-up for assembly only.

The arsenal installed in the Wallis autogyro would rival the gadget-laden Aston Martin DB5 in Goldfinger.

As expected, some ideas were just too outlandish, such as a corkscrew device mounted in the center of the rotor blade that could screw into the bottom of an enemy helicopter. Another gadget that made it into the script, but was later dropped, was a net that Little Nellie dispensed over an enemy helicopter.

The weapons that did make it into the final film were:

- two front-mounted .30 caliber machine guns

- two rocket packs each carrying 12 1.75″ “Icarus” free-flight rockets

- aerial mines launched on tiny parachutes for use when a target is directly underneath

- two “infrared” guided air-to-air missiles

- two rear-mounted smoke dispensers

- two rear-mounted flame throwers

They were mock-ups of course. In reality, the machine guns fired 60 electronically-operated blanks. However, both the rocket packs and air-to-air missiles did work, but only armed with harmless dummy warheads.

Two working autogyros were modified to house these gadgets and were shipped to Kyushu for filming.

Before we delve into the specifics of filming, editing, and miniature effects, watch the full sequence below.

Filming the Sequence

As is often the case with filmmaking, one location on film is edited together from footage shot at multiple locations around the world.

This was certainly the case when filming Little Nellie’s scenes, which were all supposed to be relatively close by in the plot.

The assembly of Little Nellie in front of Bond was shot at Pinewood Studios in London; Q’s briefing on Little Nellie’s gadgets was shot in southern Kyushu in August 1966; and its take-off was filmed on a runway in Tenpozancho, Kagoshima, around August 8. The aerial stunt was shot in Japan and Torremolinos, Spain.

Desmond Llewelyn, who played Q, managed to learn all his technical lines just in time to brief Bond. But Wallis, who was standing out of shot, recalled, “Mr. Llewelyn said his lines [perfectly, but] he pointed out all the wrong gadgets!”

On 18 September 1966, filming of the aerial sequence commenced.

Peter Hunt, the former Bond editor had exited the Bond series but was enticed back as director of the second unit for this sequence.

Four Japanese pilots flew the four SPECTRE helicopters, and in several interviews, Wallis mentions a “camera-helicopter”. There appears to have been only one camera-helicopter, piloted by the worst possible pilot imaginable: a former kamikaze pilot! Leaning out the helicopter’s side was second unit cameraman, John Jordan, who would endure a life-altering event during the filming of this sequence.

The location shoot was perilous from beginning to end for everyone involved.

Like many Bond action sequences, filming the helicopter dogfight was just as dangerous (or even more so) than the adversaries Bond faced on film.

There is some irony that James Bond himself, Sean Connery, was safe filming his scenes in front of a blue screen in London, with his feet firmly on the ground.

Hair-raising Takeoffs and Near Misses

The sequence lasts only five minutes but Bond’s double, Ken Wallis, would take off from a Japanese mountainside 85 times and be airborne for a total of 46 hours.

Filming started most days at 6 a.m. with most of the action filmed at 6,000 feet above the volcanic landscape.

Most filming occurred around Mount Shinmoe, which doubled for Blofeld’s volcano base. The scene where Bond first spots the SPECTRE helicopters via their shadows on a mountainside was shot at Sakurajima, an active volcano. In December, the shots involving the launch of rockets and the air-to-air missiles were filmed in the skies over Torremolinos, Spain because local Japanese laws prohibited the firing of rockets in midair over the national park.

Luckily the terrain in Torremolinos resembled the landscape in Kyushu, and it’s impossible to tell the difference when watching the sequence.

The smoke and flame throwers proved cumbersome on Little Nellie. At Wallis’ request, the crew filmed the cumbersome gadgets being jettisoned after “Bond” fires the smoke canisters. Unfortunately, the shot never made it into the final cut. And at the conclusion of the sequence, the smoke and flame-throwers suddenly appear on the tail ruining continuity for the eagle-eyed.

Nonetheless, the principal danger for Wallis wasn’t cumbersome gadgets but came down to the design of autogyros in general.

Little Nellie is almost always misidentified as a mini-helicopter, but the only feature an autogyro shares with a helicopter is its rooftop rotor. Little Nellie, like all autogyros, cannot vertically take off or hover. It has wheels instead of landing skids and a rear-mounted propeller just behind the cockpit which moved it forward and generated enough air current to spin the top rotor and lift-off.

She only needed 72 feet to take off, but the national park’s twisting clifftop roads were never designed as runways.

Wallis was forced to make multiple hair-raising take-offs and landings on the precarious roads that were often flanked by geological death traps.

“It was a cliff-edge road that actually turned,” recalled Wallis. “On one side was a Japanese cemetery with a big gulley before you got to it. The other was a hundred-foot drop down into the sea.”

The problems didn’t stop when airborne.

Sometimes there would be a problem with a camera, like a hair in the gate, and Wallis would have to take off and perform the stunt again. Several times, Wallis almost crashed into the camera:

“At six thousand feet, when I was doing a shot going straight towards the camera-helicopter, and once or twice I was quite close to the camera-helicopter than my intention had been. And I’d been flying long enough to realize that it was the altitude that was having an effect.”

A collision, a crash, and loss of a limb

But the biggest problem was a sudden shift in air currents which resulted in total disaster–especially for aerial cameraman John Jordan.

While leaning out of the helicopter to get a better camera angle, the helicopter below him got caught in a sudden updraft. The helicopter’s rotor cut through the landing skid of Jordan’s helicopter and severed his lower leg. Putting his craft ahead of his personal injury, Jordan tilted the camera down and filmed his leg which was attached only by skin.

The collision sent the helicopters out of control. The helicopter that collided with Jordan’s leg crashed on the mountainside below. Miraculously the pilot walked away unscathed.

Jordan’s helicopter was faced with a similar fate. At the controls was the ex-kamikaze pilot! Rather than try to crash into a target, he now had to prevent a crash, which he did, making an emergency landing with just one landing skid.

“He did a magnificent job at getting the aircraft down without rolling over because the skid on one side of him cut away and they managed to get some blocks of stone and must of helped get John out in time,” said Wallis.

A convention of surgeons was being held nearby. Jordan was rushed to this theater and they operated on him. Jordan’s foot was reattached, only to be amputated later in London.

Jordan was unfazed.

Two years later, he was back hanging from a helicopter filming the ski chase for the next Bond, On Her Majesty’s Secret Service. Unfortunately, Jordan slipped from a harness while filming an aerial scene for Catch 22 that same year, and died.

Editing is Hit and Miss

Second unit director Peter Hunt edited the sequence and ended up editing the whole film.

Hunt’s best editing is in the rather humorous introduction of Little Nellie. Through the use of both music–that suggests Little Nellie is a quirky contraption–and a series of jump cuts, the audience sees the autogyro assembled before a curious and wide-eyed Tiger Tanaka, the Head of the Japanese Secret Service.

In the late 1960s, European art cinema influenced Hollywood, which included the use of jump cuts.

Filmmakers such as Jean-Luc Goddard and Roman Polanski violated classical norms especially in editing, which Hunt picked up on and used to increase the frenetic pace of the action. Hunt would use jump cuts and other fragmented editing patterns to even greater effect for the fistfights in the next Bond film, On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, which he directed.

Unfortunately, even with Hunt’s expert hand and some of Wallis’s hair-raising swoops close to the camera, the action sequence itself has little suspense. Bond just mechanically uses each gadget to dispatch each helicopter one by one, which mirrors Connery’s performance. He’s clearly going through the motions and unable to hide his growing disinterest in the role.

Right before filming Connery told Broccoli that You Only Live Twice would be his last.

Despite the lackluster result, Little Nellie, like so many of Bond’s vehicles, became iconic. It was the second gadget-laden vehicle after the Aston Martin DB 5 and would go on to inspire Bond’s Lotus Esprit submersible (nicknamed “Wet Nellie”) in The Spy Who Loved Me.