Source Code: The Visual Influences Behind ‘The Matrix’

When The Matrix hit cinemas in 1999, audiences were introduced to groundbreaking aesthetics. The film was fresh and original–or was it? For those familiar with comics and cartoons, both western and Asian, the visual style of The Matrix wasn’t completely original.

The Matrix trilogy draws on the Wachowski’s obsession with western comic books, Japanese manga and anime, Hong Kong action and martial arts movies, and the counter-culture of ’90s computer programmers, hackers and video game players. Inherent in these traditions are certain styles of framing and lighting, an emphasis on stylized violence and choreographed movement, and an array of computer-coded imagery.

It was in the combination of these visual influences–and translating them from animation and graphics to live-action through some innovative new tech, including the film industry’s first foray into virtual cinematography–that made The Matrix unique. The Wachowskis tapped into the cultural zeitgeist, and the aesthetics in The Matrix trilogy went on to influence science fiction and action film-making in Hollywood to this day.

The sibling directors described their approach to making The Matrix as:

“Fancy Chicago fusion cooks taking a lot of things that are out there and we’re sort of mixing them in a way that hasn’t been mixed.”

So, let’s go a little deeper down the rabbit hole and delve into each of these visual influences.

And first let’s begin with the two biggest influences on The Matrix–the genre-defining cyberpunk novel, Neuromancer and the genre-defining anime film, Ghost in the Machine.

Neuromancer

It’s easy to underplay the impact William Gibson’s novel Neuromancer had on sci-fi and real-life, real-world technology. The book coined the term cyberspace and envisaged both the internet and virtual reality before they existed. It also had a huge influence on The Matrix. The bare-bones of the plot and some of the film’s big ideas have their genesis in the 1984 novel. The book’s plot revolves around Case, a data-thief who steals information by jacking directly into the matrix or cyberspace.

The aesthetic of the world in Neuromancer reads like a cross-between Blade Runner and The Matrix. Gibson may or may not have been influenced by Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner, but the Wachowskis were definitely influenced by Neuromancer.

The book’s descriptions of characters helped define the look of characters in The Matrix. Case, the book’s protagonist, is remarkably similar to Neo (Keanu Reeves) in The Matrix. He’s a 24-year-old hacker whose life is transformed when he meets a woman, who is remarkably similar to Trinity (Carrie Ann Moss). The Wachowskis give a direct nod to Neuromancer with the human city of Zion, that features in the second and third Matrix films. In Neuromancer, Zion is an orbital city central to the plot of the book’s second half.

What the Wachowskis did differently is to make the Matrix a virtual world which all humans are plugged into and convinced into believing is the real world. But the way the characters interact with the virtual and digital world is very much influenced by Neuromancer.

Ghost in the Shell

When the Wachowskis pitched The Matrix to producer Joel Silver, they did it by screening another film. That film was most likely, Ghost in the Shell, a seminal work in anime that introduced western audiences and artists to both manga and anime. The Wachowskis, who got their start writing comics, were clearly influenced by this work because its hard to watch The Matrix and not be aware of the anime’s profound influence on the film.

Silver recalled the screening:

“They showed me this animated Japanese cartoon and they said, ‘We want to do that, for real”

The visual DNA and philosophical underpinnings of Ghost in the Shell is all over The Matrix. When viewed side-by-side the similarities become obvious.

Ghost in the Shell centers on cyborg Major Motoko Kusangi, an officer in Section 9, and his hunt for “The Puppet Master”, who can hack the brains of cyborgs to bring down the power structures controlling everyone. Like The Matrix, everyone is connected to a vast artificial intelligence network. As the film progresses Motoko wakes up, like Neo, and begins to question the reality around her. The difference here is that Motoko explores what a soul is in a world where consciousness can be copied like a computer file.

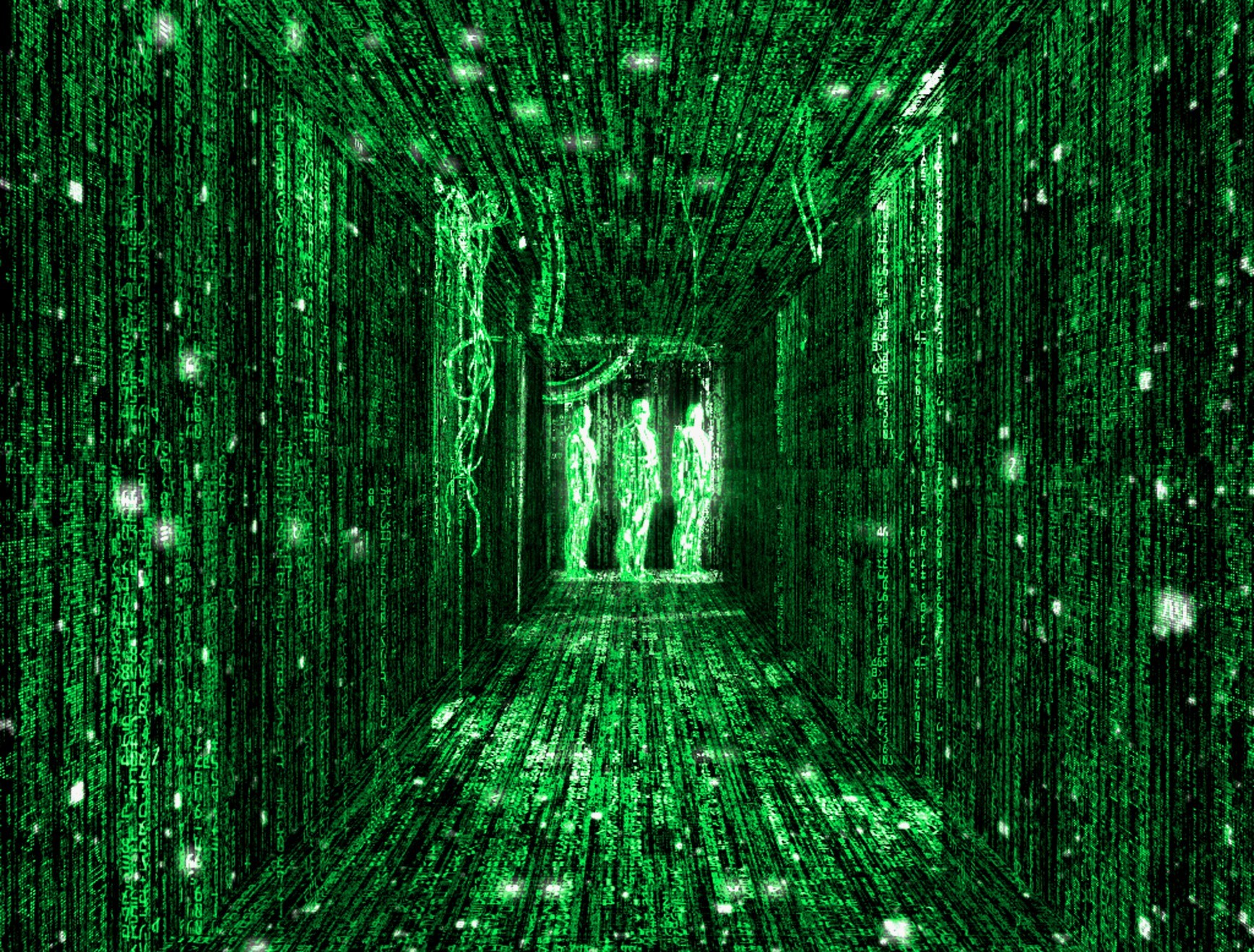

Philosophically, The Matrix follows a similar trajectory, and, in specific scenes, the film is almost exactly the same as Ghost in the Shell. If you’ve watched Ghost in the Shell, you’ll note that The Matrix has lifted two big ideas from the 1995 anime. In both films, characters jack in and out of a cybernetic world. And each film begins with green code moving across the screen before zooming in to locate someone on the cybernetic network.

But the similarities do not end there. Neo’s “superhero landing”, and even his taking cover behind a pillar as bullets tear it to pieces is directly lifted from Ghost in the Shell. The Wachowskis even copied a scene where watermelons explode from bullets fired across a public square. The video below shows most of these similarities side-by-side.

The Matrix also emulates the dystopian lighting and set designs in Ghost in the Shell. The props–the machinery–in the “real world” outside the Matrix are wiry, and robotic, which visually, can be traced back to the anime film. The Wachowskis freely admit Ghost in the Shell is a big influence. And Mamoru Oshii, director of 1995’s Ghost in the Shell, applauded the Wachowskis for being able to think like an animator and translate it into live-action.

Dark City

Ok, I wanted to break this list down into sections (anime and comics, Hong Kong martial arts, films), but as I collated the various influences on The Matrix, I found I just couldn’t do that. Quite simply, the Wachowskis borrowed significant plot elements and visuals from a book (Neuromancer), an anime (Ghost in the Shell), and a film: Dark City. These three properties have such a significant influence on The Matrix, that they really could not be separated. And all other influences that follow really just add or augment the influence of these three works.

Dark City was released a year before The Matrix with little fanfare, but its influence is all over The Matrix. John Murdoch is a Neo-like character who “wakes up” to the knowledge that his world isn’t real. He discovers that “strangers” (aliens) walk around the city unnoticed by others, just as the world of the Matrix is populated by AI androids/programs or “agents” that walk around unnoticed by those “unaware” they are living in a virtual world.

Both the “strangers” in Dark City and the “agents” in the Matrix are only known by last names: Mister Book, Mister Sleep, and Mister Wall vs. Agent Smith, Jones, and Brown. These “strangers” and “agents” all tune into the collective memory or databanks of their worlds, and speak somewhat monotonously and plainly. All “strangers” and “agents” are identifiable by their “uniform”. The “strangers” in Dark City, in their long trench coats and distinctive hats, dress like shadowy Men in Black figures from 1930s film noir. The “agents” in The Matrix dress like stereotypical FBI agents in their grey suits, ear pieces, and dark shades.

The coincidences continue when you compare the end of Dark City with the end of The Matrix Revolutions. In Dark City, John Murdoch has a showdown with the “strangers”, particularly the leader of the “strangers” while flying in the sky with buildings exploding and debris flying all over. In The Matrix Revolutions, Neo has a showdown with Agent Smith–in fact, hundreds of copies of him–while flying in the sky as it rains. There’s also another scene where Neo flies through the cityscape as buildings explode around him, leaving a trail of debris in his wake.

The similarities in both plot and visuals is far too many to be pure coincidence. The influence of Dark City on the Wachowskis is made even more persuasive by the fact that some of the same sets in Dark City were used to film the first Matrix.

Akira (1988)

It’s kind of strange to feature Akira further down the list from Ghost in the Shell, considering how formative Akira was on Oshii’s film, and the whole anime genre. Akira has a similar cyberpunk plot, and Tetsuo Shima, a central character in the anime, possesses world-changing telekinetic powers similar to the way Neo can manipulate the Matrix itself.

While there are some visual nods in The Matrix to the dystopian landscape in Akira, the more startling similarities can be found in every single chase sequence in all three Matrix films. For instance, its not a stretch to see shades of the Akira bike chase in the freeway chase in The Matrix Reloaded. Trinity on a Ducati 966 is a definite homage to Shotaro Kaneda’s motorbike and the stunts he performs.

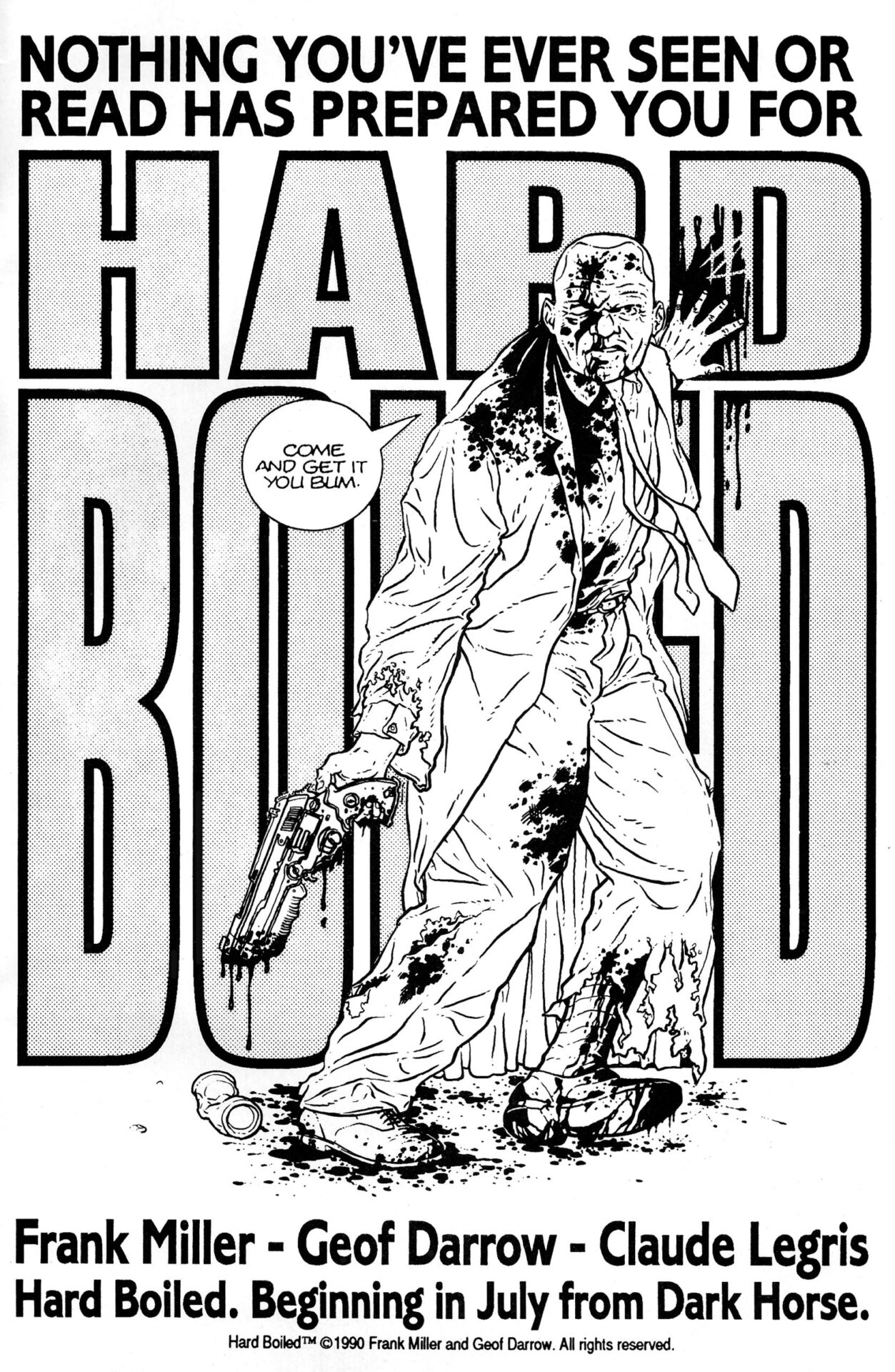

Hard Boiled (1990 Dark Horse Comic)

Frank Miller’s (300, Sin City, The Dark Knight Returns) science fiction graphic novel Hard Boiled also influenced the Wachowskis. While the novel has a dystopian setting, and the protagonist, like Neo in The Matrix, isn’t who he thinks he is, the real influence is in the visuals.

The Wachowskis were impressed by Geof Darrow’s conception of a dark and gritty dystopian Los Angeles that they let his creative imagination run wild as the conceptual artist on The Matrix. I could dedicate an entire post to his influence on The Matrix, but its suffice to say here that the Wachowskis called Darrow’s drawings “the largest influence on the world of The Matrix.” The first drawings he sent the Wachowskis were so detailed they took forever to come through the fax machine!

His conception of The Matrix’s “real world” is cold. He created the human battery farm, Morpheus’ Nebuchadnezzar spaceship, the Sentinels, and all that biomechanical medical equipment. He even helped storyboard the entire film with the Wachowskis. The directing duo loved his work so much that they commissioned him to draw their three-part comic book series, Shaolin, and brought him back as conceptual artist for Matrix Revolutions.

The Invisibles

Scores of similarities can be found in The Invisibles, a comic in which the main character is rescued from government droids obsessed with the smell of humans. Sound familiar? Agent Smith professed to Morpheus his distaste for the stench of humans. The protagonist in The Invisibles also takes a leap off a skyscraper to enter true reality. Remember Neo tests his abilities by taking a nose-dive off a skyscraper. The influence doesn’t end there; they also extend into the virtual world of the Matrix. The creators of the virtual world in The Invisibles aren’t machines, but giant insects, which are similar to the insectoid, squid-like sentinels that terrorize Zion and human ships like the Nebuchadnezzar in the Matrix films.

Hard Boiled (1992 John Woo film)

This film has no connection with Frank Miller’s comic, except that they share the same name, and both had a big impact on The Matrix. The Wachowskis love Hong Kong action films, but John Woo’s film is different. It’s the film that attracted Hollywood’s attention to Woo. The choreographed, slo-mo gun play Woo is known for is in fine form in this film. The choreographed gun play and the stylized martial arts are brought together like an onscreen ballet. It’s easy to see the strong influence on the fight scenes in The Matrix. Hard Boiled is the genesis of the long tracking shots, slow motion bullets and flying debris, and first person perspectives that pervade the Wachowskis’ Matrix trilogy.

Speed Racer and Michel Gondry

The most astounding visual effect in The Matrix is undeniably bullet time. There has been much debate over the years about exactly where the idea originated from. The reality is that the precursor to bullet time can be found in multiple places. Bullet time is the combination of two elements: a fluid camera movement that sweeps through the action, and slowed down movements of characters and objects, like flying bullets.

For the sweeping movement of the camera, the Wachowskis may have been influenced by the introduction to the animated series, Speed Racer, which the directors turned into a live-action film in 2008.

In the TV series intro below, you can see that the animation sweeps around the race car showing it from multiple angles in one fluid shot.

John Gaeta, the visual effects supervisor on The Matrix trilogy, developed this further with his innovative multi-camera set-ups shaped in S-curves, 180-degree arcs, or loops. Dozens of cameras set up this way created a seamless effect through either the curves, arcs, or loops as if it was one camera moving through or around the action.

For the slowing down of bullet effects and other objects, Gaeta said he was influenced by the work of Otomo Katsuhiro, who co-wrote and directed Akira, and director Michel Gondry. He told Empire Magazine:

“His music videos experimented with a different type of technique called view-morphing and it was just part of the beginning of uncovering the creative approaches toward using still cameras for special effects. Our technique was significantly different because we built it to move around objects that were themselves in motion, and we were also able to create slow-motion events that ‘virtual cameras’ could move around – rather than the static action in Gondry’s music videos with limited camera moves.”

While Gaeta states Gondry’s “music videos” influenced bullet time, the genesis for the live-action effect most likely originated in Smarienberg, Gondry’s advert for Smirnoff Vodka.

Hong Kong Martial Arts

The Matrix pushed action choreography to a whole new level. Nonetheless, it has its roots in Hong Kong Martial arts. All that fancy foot-work, and gravity-defying martial arts moves came from fight choreographer, Yuen Woo-ping.

Woo-ping uses a mixture of martial arts techniques which include Ju Jitsu, Savate, Kenpo, Taekwondo, and Drunken Boxing. In The Matrix, these are shown on a computer terminal as they uploaded into Neo right before he faces off against Morpheus in the training simulation.

The Wachowskis, inspired by Yuen’s work on Fist of Legend (1994), hired him as martial arts choreographer on The Matrix. He continued to impress with his work on Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon a year later. After the Matrix sequels, he caught the eye of Quentin Tarantino, who hired him for Kill Bill (2003).

Even Woo-ping, though, was influenced by martial arts superstar Bruce Lee. The Matrix pays homage to Lee’s stunning fight choreography in films like Way of the Dragon (1974). Compare the arm work of Neo, above, with that of Bruce Lee below.

Spaghetti Westerns

No mention is made of the influence of spaghetti westerns on The Matrix. The face off between Neo and Agent Smith at the end of the Matrix is like those classic Sergio Leone showdowns in The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. The subway is The Matrix’s version of the streets of some Old West town. And the flying sheets of newspaper are The Matrix’s equivalent of the tumble weeds in many old westerns. Even the close-ups of Eastwood’s hand reaching for his gun is copied in The Matrix when Agent Smith clenches his fist at his waistline. As are the long black trench coats worn by Morpheus and his team.

After reviewing all these visual influences on The Matrix, you might conclude the Wachowskis are plagiarists. But on re-watching the trilogy, it really does stack up as a singular work in its own right. The technological innovations alone make the film a work of art, and those innovations revolutionized filmmaking for the next twenty years.

Filmmakers have always drawn from other artists. Most of Quentin Tarantino’s films are a homage to various genres: martial arts in Kill Bill 1 and 2; the western in Django Unchained and The Hateful Eight. Everything from the musical them to characterization has its roots in these genres in a Tarantino film. Even someone as unique as Christopher Nolan has mined the James Bond films to create scenes in both Inception and The Dark Knight Rises, and lets not forget that Inception also borrows from The Matrix.

So its not that these filmmakers plagiarize other filmmakers by borrowing from their films; its how they recombine ideas into something fresh and original. Without the influence of manga, anime, and the work of Michel Gondry, we would never have experienced “bullet time”.

Furthermore, The Matrix distinguishes itself by being rooted in the real world. While its a product of its time, the series is also relevant today as we struggle with social, economic, and governmental control systems. Now that virtual reality has reached capabilities that can disconnect us from the real world both in our personal use, and even in film production (StageCraft), The Matrix is more relevant than ever.