Alfred Hitchcock Subverted 1 Common Thriller Cliche In The Crop-Duster Sequence in North By Northwest

The man gunned down by thugs in a car while standing on the street corner in the middle of the night is a cliche Hitchcock wanted to subvert in North By Northwest. In the process, he created an often-used cliche of his own.

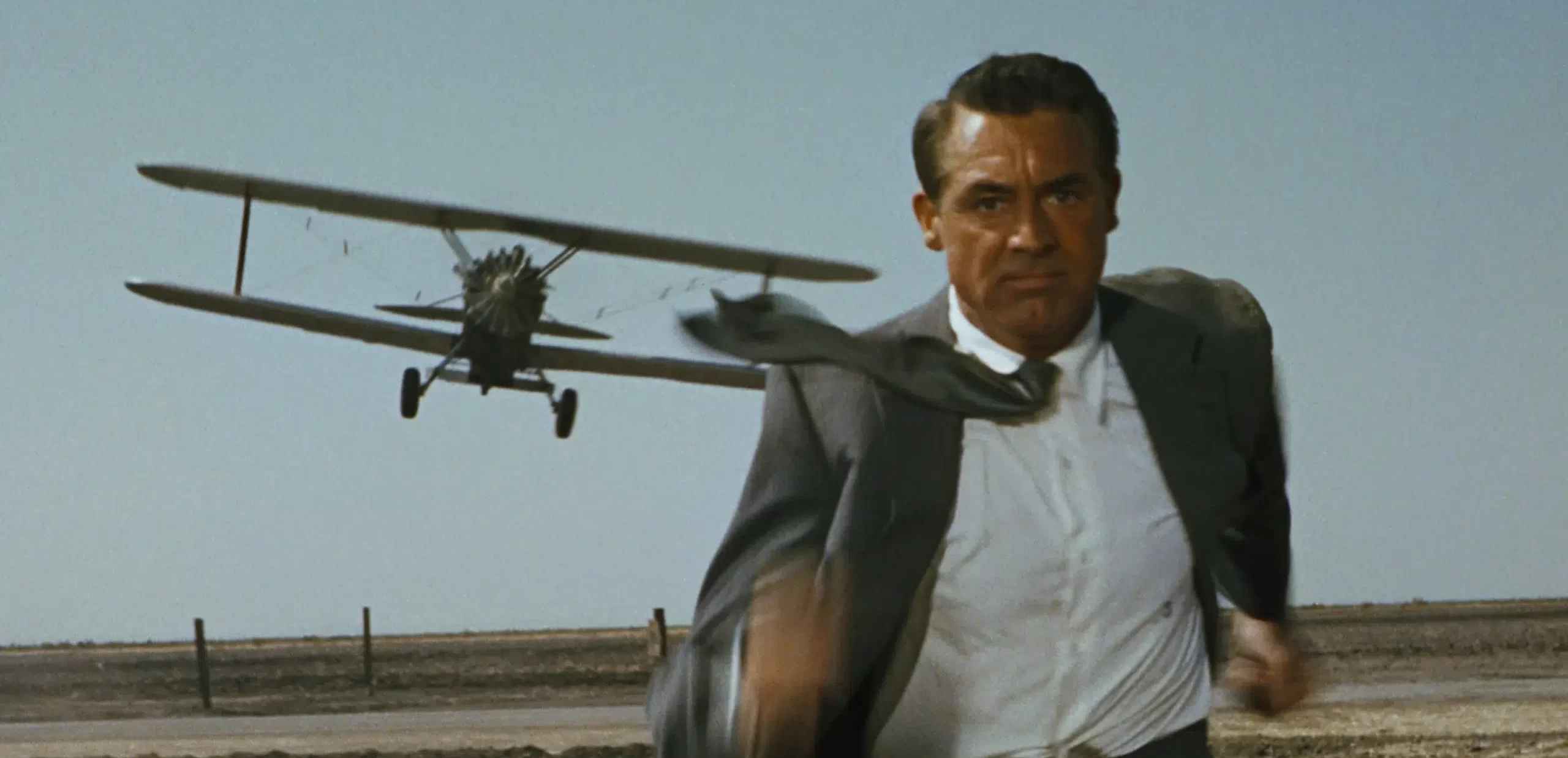

It’s an understatement to say that the indelible image of Cary Grant running from a low-flying crop dusting plane is iconic.

Even those who have never seen North By Northwest know the image and the sequence. What many do not know is the sequence’s success relies on a suspenseful six-minute buildup to the actual crop duster chase.

In North By Northwest, Grant’s character, Roger Thornhill, a fast-talking advertising executive from New York, is mistaken for George Kaplan and spends most of the film being chased by villains and the CIA.

Midway through the film, Thornhill is drawn to this location in the middle of nowhere to hopefully meet Kaplan and clear up this misunderstanding. For six minutes Thornhill is passed by cars, a truck, and even engages in a conversation with a man waiting on the other side of the road. Every encounter increases the suspense to the final reveal that it is an anonymous pilot flying a crop-duster that has been sent to kill him. Not Kaplan.

This six-minute buildup, and the crop-duster chase itself, last about ten minutes. We’re going to analyze this whole sequence, paying particular attention to the first six minutes which Hitchcock said came from his desire to subvert the tired cliché of a man lured to a dark street corner only to be gunned down by the anonymous occupants of a slow-moving car.

Subverting a cliche

Hitch told Truffaut in their famous interview:

“I found I was faced with an old cliché situation: the man who is put on the spot, probably to be shot. Now, how is this usually done? A dark night at a narrow intersection of the city. The waiting victim standing in a pool of light under the street lamp. The cobbles are ‘washed with the recent rains.’ A close-up of a black cat slinking along against the wall of a house. A shot of a window, with a furtive face pulling back the curtain to look out. The slow approach of a black limousine, et cetera, et cetera. Now, what was the antithesis of a scene like this? No darkness, no pool of light, no mysterious figures in windows. Just nothing. Just bright sunshine and a blank, open countryside with barely a house or tree in which any lurking menaces could hide.”

His solution to this tired cliche was to have Roger Thornhill lured to the opposite location, at the opposite time of day, where the colors, lighting, sounds and general conditions were completely different.

There’s no dark alley, no place for a villain to hide for miles. Thornhill can see everyone who approaches. But he’s also exposed and vulnerable which Hitchcock would take advantage of in every possible way.

We’re going to break down how Hitchcock subverted this cliché and created one of his own that has been used in many films and TV shows to come.

Before we begin the analysis, it’s important to point out that Hitch never wasted one shot. He even acted out the whole sequence with screenwriter Ernest Lehman in Lehman’s living room. Then Lehman wrote it down in the script including almost every camera angle that appears in the final sequence.

The sequence was then meticulously storyboarded or written into a detailed shot list (There’s some contention over whether storyboards that exist were made before or even after the sequence was shot to generate publicity. But a detailed and verified shot list and diagram used by cinematographer Robert Burkes was used on location).

Everything Hitchcock uses is to effect: the location, the color, the lighting, costumes, vehicles used, the pairing of objective and subjective camera shots to simulate Thornhill’s POV, the use of silence and natural sounds and the sudden use of the soundtrack at the end. We’ll keep each of these in mind as we explore those crucial six minutes of build-up and the final crop-duster chase itself.

Using visual language to promote isolation

There’s a profound sense of isolation. As a New York ad executive, Thornhill is far from his natural environment.

Not only is this sequence the opposite of that thriller cliche, but it is also the opposite of the hustle and bustle of New York and his journey across the country. This is completely foreign territory for a man who’s natural uniform is a suit.

The establishing shot is a crane shot high above the road.

Thornhill is reduced to almost a speck, with the vast flat landscape stretching into the horizon beyond him. There’s a sense that Thornhill is in danger from the first establishing shot.

Here, Hitchcock employs visual language that is the opposite of the cliched lonely man on a street corner. Thornhill isn’t in a built-up city center; he’s on the loneliest rural road Hitchcock could find in America. Thornhill isn’t standing in the rain in the dead of a cold night; he’s standing under the scorching heat of a bright summer’s day. Thornhill isn’t surrounded by dark alleyways and buildings in which a threat can loom and hide; he’s standing out in the open in a flat landscape that stretches for miles in every direction.

That isolation is expounded by the browns, the dry heat, the high-key lighting to simulate the Sun at its highest peak in mid-afternoon. This environment is uninviting, unfriendly, and potentially hostile. It’s desolate.

All of this is communicated instantly to us through one establishing shot.

The visual language Hitchcock uses might be the opposite of that old cliché, but the effect is the same. We sense Thornhill’s isolation and there is a pervading sense of danger, just like the tired trope of the man standing on the street corner in the middle of the night.

Turning Thornhill into a target

Hitchcock deploys other visual aids to increase the sense of Thornhill’s isolation. Still dressed in his grey suit, Thornhill couldn’t be more different than the farmers and rural folk who live in the area.

“You have prairie-like land around you and a man in a business suit,” Hitchcock recounted in a 1969 interview. “See, there’s your immediate counter-point.”

We just instinctively know he’ll be a target. He doesn’t belong here. That New York suit is the equivalent of having a target painted on his back. It’s a simple image—a simple device–that Hitchcock uses to signal to the audience the coming danger without saying a word.

Hitchcock has Thornhill look in every direction. It gives us a sense of the location, but it also establishes that the threat could come from any direction. Thornhill spots the crop-duster in the distance, but its so far away that we do not connect it as a possible threat.

What could be more normal than a crop-dusting plane dusting crops?

Besides we expect the threat to come by road, established by that old cliche, and the fact that Thornhill is standing on a roadside. This misdirection is established by Thornhill’s proximity to the road, while the real threat is harmlessly miles away in the distance.

Nonetheless, Hitchcock has, narratively, established the threat by giving us a glimpse of the plane and also the other important feature of the upcoming chase: the cornfield in which Thornhill briefly takes refuge.

Subverting a tired cliché by presenting a number of threats that turn out to be nothing

Hitchcock spends most of this six-minutes presenting possible threats on the road.

“Motion picture mood is often thought of as almost exclusively a matter of lighting, dark lighting.” Hitchcock explained. “It isn’t. Mood is apprehension. That’s what you’ve got in that crop duster scene…he looks around him and cars go by. So now we start a train of thought in the audience. ‘Ah, he’s going to be shot at from a car.’ And even deliberately, with tongue in cheek, I let a black limousine go by…Now, the car. We’ve dispensed with the menace of possible cars or automobiles.”

Hitchcock gives us not one but four approaching vehicles.

Thornhill, rather expectantly, watches the first car approach. It takes a full eight seconds for the car to approach from the distant horizon and speed past Thornhill, who peers through the windscreen as the car zooms past. He watches for another five seconds as the car zooms away from him into the distance

That’s not Kaplan.

The car’s a relatively non-threatening white sedan.

Then, another car approaches from the opposite direction of the first.

This car is more threatening than the first. Black, hearse-like, and moving a little slower than the first car. Thornhill is on edge. This car would be the type of vehicle to approach a man standing on a darkened street corner. But this car soon passes into the distance just like the first. The “black limousine” Hitchcock refers to.

Then, a truck passes. Each vehicle is bigger than the last. Hitchcock cuts the tension with a little humor. The truck billows up a cloud of dust over Thornhill as it passes. The biggest threat any of these vehicles pose.

Finally, another car comes out from behind a cornfield and turns onto a dirt road that intersects with the main road and leads directly to where Thornhill stands.

“Now a jalopy comes from another direction, stops across the roadway, deposits a man, the jalopy turns and goes back. Now he’s left alone with the man. This is the second phase of the design. Is this going to be the man? Well, they stand looking at each other across the roadway.”

It’s really the different direction from which this car comes that makes us wonder if this is Kaplan. Once again it’s deliberate. It takes a good 25 seconds for the car to approach and stop on the other side of the main road opposite Thornhill.

Thornhill is curious. The audience is curious. Surely this is Kaplan.

A man gets out and stands almost opposite Thornhill on the other side of the road. This has to be the man Thornhill has come to meet.

Hitchcock gives us that wonderful wide shot of the two men staring at each other. Another excruciating amount of time passes. A second is a long time in a suspense scene, but never drags when utilized to effect.

It’s as if both men are waiting to meet someone.

Throughout this whole scene so far, Hitchcock has employed a unique POV style of shooting and editing which involves first seeing Grant looking at something, then what he is looking at through his eyes.

This style of shooting and editing is used for the first 48 shots by the time Thornhill decides to cross the road and approach the man on the other side. We’re more intimate with Thornhill as a result. The effect helps to put us in Thornhill’s shoes to a degree.

As Thornhill crosses the road towards the man, the camera now moves closer mimicking Thornhill’s POV as he approaches.

This elevates the suspense and really makes us consciously aware for the first time that we’re seeing out of Thornhill’s eyes.

It’s pure misdirection of course because Thornhill soon discovers in the sequence’s only lines of dialogue that the man is waiting for the bus.

The red herring temporarily reduces tension until the man delivers that one fateful line of dialogue as he gazes at the crop duster in the distance:

“That’s funny. That plane’s dusting crops where there are no crops.”

With that one line of dialogue, Hitchcock increases the suspense ten-fold the sudden realization that the crop-duster plane is the threat. The line of dialogue is another device Hitch deploys. The man delivers the line just as the bus arrives. After he leaves, Thornhill is alone.

That line delivers a sudden shock to the audience as they realize the distant crop-duster is the threat. Their attention turns to the crop duster which suddenly changes direction. This signals a change from the ordinary to the extraordinary, as Hitchcock explained:

“Now the next question was: if it’s so ordinary as this, now you begin to gradually shift into the extraordinary because you bring up the question, naturally, there is a plane dusting crops where there are no crops. So immediately your audience are beginning to sit up.”

Hitchcock described the idea of a dive-bombing crop duster as purely gratuitous. It has no real narrative purpose other than to entertain.

But it’s effective.

More effective because the audience works out the threat a few seconds before Thornhill, who only gets it when the plane flies straight toward him. This is another deliberate device Hitch uses in raising the suspense. We’re on the edge of our seats wanting Thornhill to wise up and get out of the way of the dive-bombing plane.

The Crop-Duster Attack

Now we come to the actual crop-duster attack. Six minutes of suspense helps turn this attack in an icon of cinema.

In comparison to the cliché Hitchcock deliberately subverts, the fast-moving plane is a replacement of the slow-moving black car creeping up on the man at the street corner. Instead of a man firing a machine gun from the back seat, the plane is equipped with machine guns in the cockpit. And the pilot remains just as anonymous and unseen as the back seat gunman behind the darkened car windows.

The origin of this scene comes from a source other than Hitchcock: North By Northwest‘s screenwriter Ernest Lehman.

Originally, Hitch had the unusual idea of having Thornhill pursued by a tornado. Lehman asked Hitch how he was going to recreate a realistic-looking tornado with special effects and then suggested the crop-duster plane instead.

Hitch loved the idea and built the suspenseful sequence around it.

Lehman also suggested the cornfield (originally a wheat field) for Thornhill to hide in as his only refuge.

The crop-duster’s pilot flushes out its quarry by dusting fertilizer all over Thornhill.

Hitchcock had a rule: if you use something in a sequence, it must perform its function.

“One rule I have, one very essential [rule]. If you have a crop duster, you must let it dust. Therefore, he runs into the corn and hides in the corn. And what does the airplane do? It dusts the crops. It does its job on a man and not on the crops.”

He’s back in the open, and tries to flag down a truck like he did with a car early in the chase.

Here, it’s interesting that Thornhill tries to flag down cars and trucks in his bid for safety after they were originally the source of suspicion in the first few minutes of the sequence. Hitchcock likes symmetry in his sequences, but he also adds that final shock when Thornhill is almost hit by the truck as he falls to the ground to avoid collision with its bumper.

The crop-duster then misjudges its final dive-bomb and crashes into the truck’s tanker and explodes. Thornhill is saved by an accident.

It’s only then that the soundtrack plays to highlight the climax of the sequence. This ten minute sequence has been mostly silent, punctuated by sounds from passing cars, the crop-duster, and the few lines of dialogue.

Silence is a principle feature in building the suspense of the sequence. After seeing a rough cut of the sequence, Lehman urged Hitch to increase the sound of the sound effects. Hitch ignored the advice as he wanted the images to speak for themselves. In fact, the sound effects are more natural, more in tune with what audiences expect today, than some of the exaggerated sounds they were used to at the time. Hitchcock’s decision means the sequence hasn’t dated much today.

The editing of the sequence is also unique for the time. In their famous interview, Francois Truffaut noted that instead of increasing the tempo of the shots during the action, which is characteristic of action sequences, Hitch uses equal shot duration for every shot in the crop-duster attack.

Hitchcock said: “Here you’re not dealing with time but with space. The length of the shots was to indicate that a man had to run for cover and, more than that, to show that there was no cover to run to. This kind of scene can’t be wholly subjective because it would go by in a flash.”

Hitchcock follows an objective shot of the plane approaching with Thornhill’s point-of-view of the same approach. It was necessary to show the plane to the audience before Thornhill sees it, otherwise the plane would approach too fast and be in and out of the frame before the audience sees it.

The audience sees what Thornhill doesn’t yet see, which just adds more suspense because we know where the plane is coming from before Thornhill does.

By today’s standards, the sequence appears slow-moving. But the pairing of objective with subjective—from Thornhill’s point-of-view—raises the suspense considerably. And Hitchcock is about suspense more than action.

Hitchcock will use it to a slightly different effect during the crop duster chase, when we see the plane approaching right before Thornhill does.

The pairing of objective with subjective shots is used four times to affect in the crop-duster sequence. First, just after Thornhill is dropped off by the bus and surveys his surroundings. Second, when Thornhill approaches the man standing on the opposite side of the road. Third, when Thornhill is chased by the plane. And finally when Thornhill is almost run down by the truck at the end of the sequence.

This subjective-objective pairing of shots emphasizes either important information for the audience; a moment of heightened suspense; or, in the case of the final moment, startles the audience with a final shock. It is as much an editing trick as a perspective shift, and helps considerably with pacing at just the right moment.

The crop-duster sequence became the template for many action sequences that followed. The most notable is the helicopter attack in the second James Bond, From Russia With Love, which is the most Hitchcockian Bond film in the franchise.

Next time we’ll look at why the helicopter attack in that film has been unfairly written off as a poor imitation of the crop duster sequence in North By Northwest, and while it is innovative in its own respect.