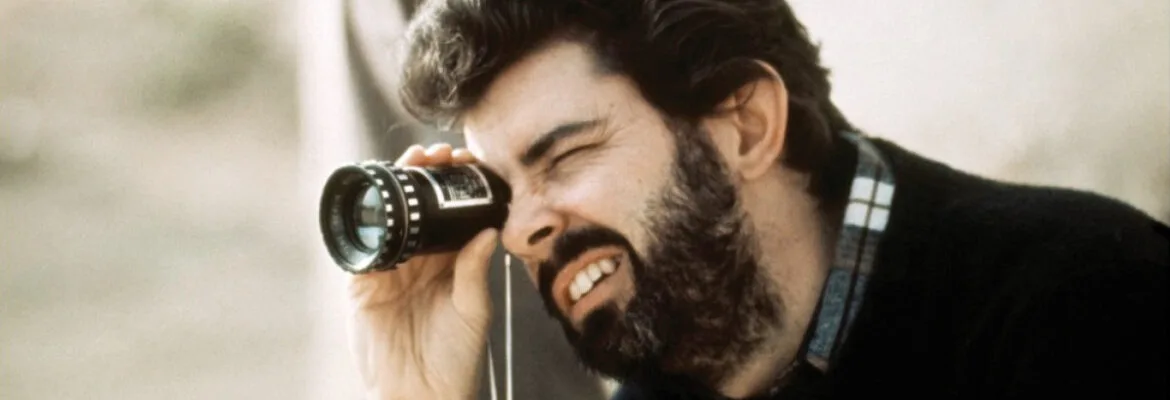

Before Coppola, George Lucas Planned To Direct ‘Apocalypse Now’ Like a Black And White Documentary

Apocalypse Now earned its status as the greatest war movie of all time, a brutal and darkly comic examination of the double standards of war. Director Francis Ford Coppola decried notions the film is an anti-war film. The film is more clever than that in its depiction of the psychology of those in conflict. The film is politically ambiguous leaving it up to the individual to make up their own mind.

But Apocalypse Now could have been a very different movie. The first filmmaker slated to direct was George Lucas working from a screenplay written by John Milius. The Vietnam War was a hot topic for aspiring young filmmakers learning their craft in the Sixties and Seventies. And Lucas was just as anti-war as he was against the Hollywood movie system. Lucas of course would go on the make his own film reacting to the Vietnam War called Star Wars, and his early work on Apocalypse Now would go on to influence his space opera set in a galaxy far far away. But his work on Star Wars–and other films– does not exhibit the political ambiguity that made Coppola’s film so impactful. It is doubtful his version of Apocalypse Now would have anywhere close to the impact Coppola’s version did.

Coppola, Lucas, and Milius have a long history that takes them all the way back to film school. Milius was working on his screenplay for Apocalypse Now in film school. The script was based on Joseph Conrad’s novel, Heart of Darkness, about a man who journeys up the Congo River on behalf of a Belgian trading company. Far upriver, he encounters the mysterious Kurtz, an ivory trader who exercises an almost godlike sway over the inhabitants of the region. Milius talked endlessly with fellow student, Lucas, about making a movie on the Vietnam war and saw Conrad’s novel as the perfect vehicle. They would frequently hang out with Coppola in his Burbank office on the Warner Brothers lot. They would all talk about their dream projects, and Coppola remembered, “I recall George [Lucas] and John [Milius] mentioning a lot of guys who were returning from Vietnam, bringing word of the craziness of it, the drugs, the hallucination, the surfing…And they were cooking up a script that John would write for George [to direct].”

The idea came out of Lucas’s musing over doing a film featuring hand-to-hand combat with a plane, an idea that would end up in the gruesome scene in Raiders of the Lost Ark in which a Nazi gets his face sawn off with a plane’s propeller. But before Indiana Jones and before Star Wars, Lucas had originally envisioned himself as a documentarian. Even after finishing his first feature, THX 1138, Lucas planned a return to documentaries. The film had garnered critical success but performed dismally at the box office. Lucas and Milius were unfazed, primarily because their plan was to shoot Apocalypse Now like a black-and-white documentary on 16 mm “in the rice fields between Stockton and Sacramento.”

The proposed shoot was the beginning of Lucas’s working relationship with friend Gary Kurtz, who would go on to produce American Graffiti, Star Wars, and The Empire Strikes Back. Kurtz took a trip to the Phillippines on a location recce, while Milius suggested they shoot in Vietnam in the midst of the conflict. He said:

“We were going to make Apocalypse Now for $1.5 million in Vietnam. We got all these connections; we got people who were generals in the Air Force, and people who were going to help us get around. I remember all these guys around Francis at the time who were hippies and extreme political radicals–they all wanted to go make this movie. They wanted to go to Vietnam without any protection whatsoever and hop around through the minefields. It came pretty close, but then the studio started saying, ‘Why are we sending those hippies over there? They’re a bunch of nuts. Some of them will be killed. There’s a real war over there.’ So they stopped us. I mean, this was a time when there were riots in the streets about the war, and a studio executive is the last person who’s going to want to get invovled in the middle of that. Hollywood isn’t exactly known for its social courage.”

Lucas planned to shoot Apocalypse Now like the film, Battle of Algiers, which used a hand-held Cinema Verite style capturing “realism” without artistic effects. While in pre-production, Lucas took a break to film American Graffiti in 1973. Very swiftly, Lucas was being taken in the opposite direction from his documentary aspirations. American Graffiti made over $100 million at the box office, a rare feat in the early Seventies. Coppola, meanwhile, had been circling Milius’s screenplay, and in the Spring of 1974, he met with co-producers Fred Roos and Gray Frederickson to talk about bringing his vision of Apocalypse Now to the big screen.

According to Milius, Lucas was no longer interested in filming in the jungle. His attention now turned to acquire the rights to the Flash Gordon serials which had enthralled him as a child. His bid for the rights was rejected, and now his time was consumed with creating his own space opera, Star Wars.

Lucas recalls it differently citing his continual fight to get better terms from Hollywood studios:

“I couldn’t get the same terms Francis had gotten at Warners; it was much less. But he was determined to hang on to the same number of points [otherwise known as percentage of the profit], his old number, so whatever Columbia took, I had to give up. My points were going to shrink way down, and I wasn’t going to do the film for free. He had the right to do it, it’s in his nature, but at the same time I was annoyed about it…We couldn’t get any cooperation from any of the studios or the military, but once I had American Grafitti behind me I tried again and pretty much got a deal with Columbia. We scouted locations in the Phillipppines and we were ready to go”.

However, Columbia wanted all the rights that Zoetrope had, and according to Lucas, “the deal collapsed … and when that deal collapsed, I started working on Star Wars.” Editor Walter Murch believed Lucas directed American Graffiti to prove to the studios he could make a commercial success in order to secure funding for Apocalypse Now. But the subject matter and the documentary style of the proposed film turned the studios off the idea.

After reading the screenplay for Star Wars, apparently, Coppola gave Lucas an ultimatum–Apocalypse Now or Star Wars. Lucas chose Star Wars. Lucas had borrowed ideas from Apocalypse Now for Star Wars. The idea of the Vietnamese withstanding the onslaught of the superior US forces and winning served as inspiration for the Rebels fighting the Galactic Empire in Star Wars. With Lucas out, Coppola took control of Apocalypse Now.

Despite turning Apocalypse Now down, Lucas expressed disappointment in losing the film. “All Francis did was take a project I was working on, put it in a package deal, and suddenly he owned it.” Lucas’s response smacks of bitterness because Coppola would enter into a considerably fraught-filled production, and besides, Coppola would change Milius’s script considerably and move in the opposite direction of Lucas’s planned hand-held 16 mm black-and-white doco.

Zoetrope owned the screenplay, so Coppola had to either make it or forget about it. Initially, he asked Milius to direct because he needed to make a big hit so he could make all these art house films he really wanted to make. When Milius refused, Coppola decided to make it himself. Coppola went in the opposite direction to Lucas’s planned documentary-style version. He originally conceived of an epic like Guns of Navarone to make that big money to finance his smaller art films.

Coppola would change much of Milius’s script so it was more faithful to Conrad’s original novel. Coppola transposes much of the novel set on the Belgian Congo to Vietnam. “You have to realize, when I was making this I didn’t carry a script around,” he told The Guardian. “I carried a green Penguin paperback copy of Heart of Darkness with all my underlining in it. I made the movie from that.”

Coppola began production in 1974 for a planned theatrical release on July 4th, 1976. But the problematic production took 238 days to shoot in the Phillippines. Replacing Harvey Keitel with Martin Sheen just a few days into filming was only the beginning of his problems. Sheen would have a near-fatal heart attack. Bigger problems loomed with Marlon Brando, notorious for ridiculous demands. He turned up overweight and unprepared demanding his character’s name be changed to Col Leighley, only for him to change his mind and change it back to the original name Kurtz. In addition, the cast and crew were taking large amounts of drugs. Apparently, Dennis Hopper only agreed to make the movie in exchange for an “ounce of cocaine.”

There were problems with Filipino helicopter pilots. The helicopters and their pilots rented from the Filipino government were often called away to fight in real skirmishes against insurgents in southern Phillippines. The pilots were often different from rehearsal to rehearsal and helicopters had to be repainted twice daily from Filipino to US colors. To top it all off, a typhoon swept away most of the set.

Coppola was waging war himself. And he wasn’t going to retreat. In 1975, he staked his own property Inglenook, which he had purchased from the money earned making The Godfather, to keep production going in the Phillippines. The gamble paid off. The film was released in 1979

But what seemed like an ill-fated production came through under Coppola’s leadership. Although he is known for his Napoleon-sized ego, Coppola is likely one of the few directors that could have pulled a film together in these conditions and turned it into a masterpiece of cinema. Coppola shares Lucas’s desire to be independent of the studio system, and both marshaled their own money to have creative control over their projects. But Lucas, who struggled with dealing with British film crews and giving directions to actors, would likely have faltered if he made Apocalypse Now. The experience might have finished him off and we never would have got Star Wars.