Darth Vader In Rogue One: The Secrets Behind That Badass Corridor Scene

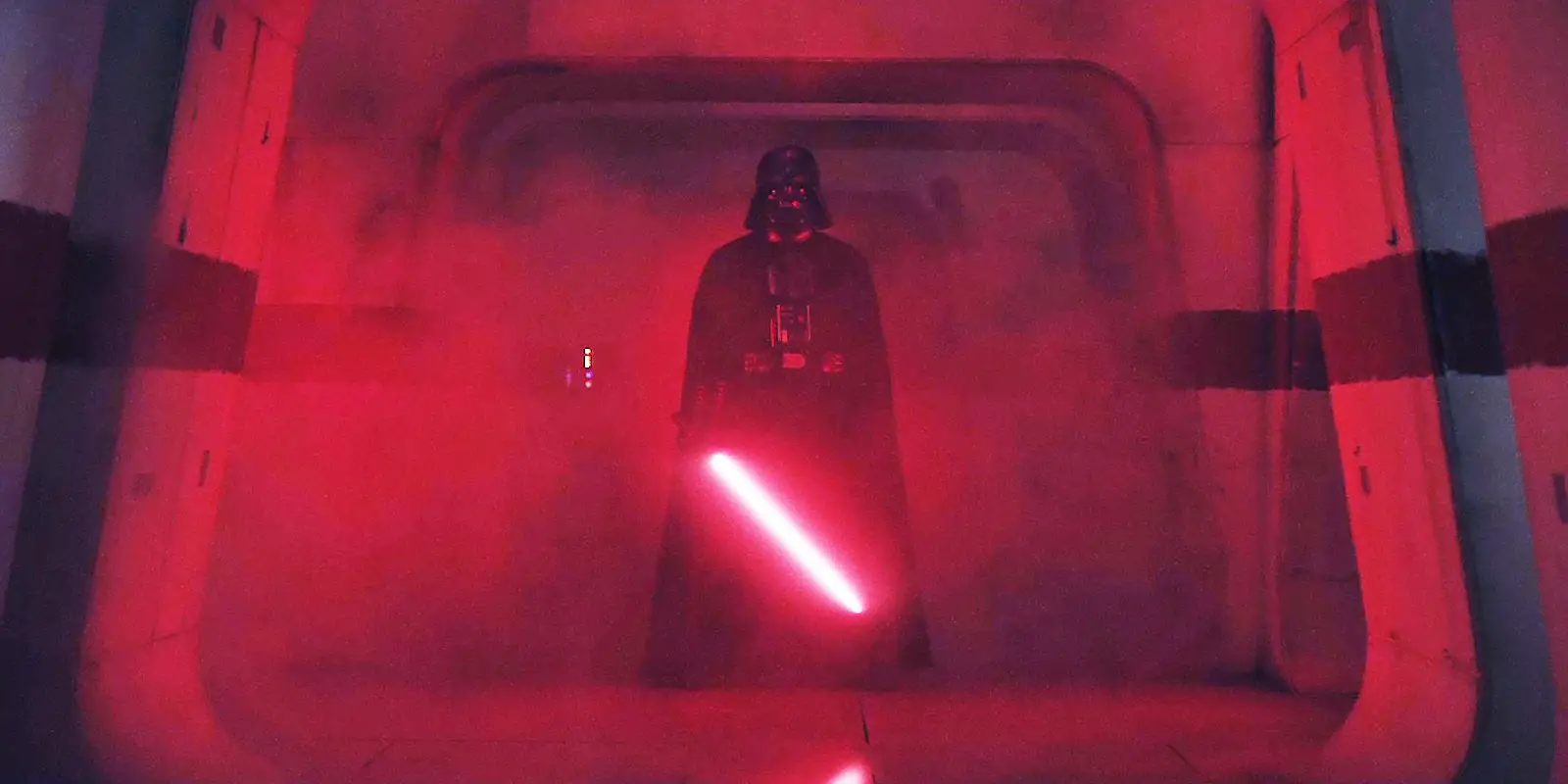

When the lights dimmed in cinemas in December 2016 and the closing moments of Rogue One: A Star Wars Story played out, audiences didn’t yet realize they were about to witness one of the most electrifying sequences in the entire Star Wars saga. The now-legendary corridor scene—Darth Vader igniting his crimson lightsaber in a darkened hallway and cutting down terrified Rebel soldiers—lasts less than two minutes, yet in less than a decade it is considered one of Darth Vader’s best moments on screen.

A late addition to the film, Vader’s horror-inspired corridor scene was dreamed up in the final months of production by director Gareth Edwards, writer Gary Whitta, and editor Jabez Olssen. What began as a simple desire to bridge Rogue One and A New Hope evolved into a moment that clarified what makes Vader such a terrifying villain–delivering a powerful, tension-filled scene that underscores how close the Rebels came to losing the Death Star plans after already sacrificing so much to steal them.

But how was this scene devised and made? The story behind the corridor scene’s creation is about fusing modern filmmaking techniques with old school practical effects and sensibilities to match up with the original film–A New Hope–created nearly 40 years earlier.

Inside Vader’s castle on Mustafar

A Scene Born Late in the Game

By the time Rogue One entered post-production, the film already had its bleak, sacrificial ending. Jyn Erso and Cassian Andor had transmitted the Death Star plans to the Rebel fleet, dying in the process. The story dovetailed cleanly into A New Hope. But according to both Edwards and Lucasfilm’s senior creative executive Kiri Hart, the film felt like it needed “just a bit more punctuation.”

The initial version of the ending merely showed a Rebel officer running the Death Star plans down a hallway and handing them off before cutting to the Tantive IV’s jump to hyperspace. It worked narratively—but emotionally, it lacked the intensity audiences expected from Star Wars.

It was editor Jabez Olssen who first suggested that Vader’s presence could be used to “put an exclamation mark” on the ending. The idea snowballed. Edwards, Hart, and Whitta began brainstorming how Vader might appear without undercutting the finale’s emotional core. The concept evolved: what if Vader arrived just seconds too late, slaughtering the Rebels as they desperately tried to escape with the plans?

The scene was written, storyboarded, and shot months after principal photography wrapped—essentially a reshoot that would redefine how the film was remembered.

Storyboarding the Nightmare

The first visual conception came from ILM’s in-house storyboard artists and Edwards himself, who had a background in visual effects and liked to “draw shots like puzzle pieces.” Edwards wanted the sequence to feel like a horror film, not a traditional action set-piece.

In early sketches, the corridor was almost completely dark. The audience would see nothing at first—just the sound of Vader’s breathing. Then, in a flash, the red blade would ignite, illuminating his form. The Rebels would panic, fire blaster bolts, and watch them reflect harmlessly off the Sith Lord’s lightsaber.

Every beat of the sequence was plotted for maximum escalation:

Silence as the Rebels await boarding.

A mechanical breath—the signal that death has arrived.

The lightsaber ignition—a visual explosion of red.

Panic and slaughter—Vader advancing, unstoppable.

Desperation—the last Rebel passes the plans through a door before dying.

The tension mimics the structure of a horror climax: mounting dread, the unstoppable killer, and a narrow escape that sustains the larger story. Edwards often cited Alien and Jaws as tonal references—moments where “you barely see the monster, but you feel its power.”

Building the Corridor

The set for the Rebel blockade runner corridor was an exact replica of the Tantive IV hallway from A New Hope, painstakingly rebuilt by production designer Neil Lamont and the Pinewood Studios art department.

Lamont had access to original production blueprints from 1976 as well as digital scans from the A New Hope restoration project. The decision to use practical sets rather than digital composites was deliberate—Edwards wanted the tactile authenticity of 1970s Star Wars design: “You can feel the dirt, the grease, the fear,” he said in interviews.

To create the cramped sense of entrapment, the set’s ceiling was lowered and lighting rigs hidden behind translucent panels. Edwards shot with anamorphic lenses on the ARRI Alexa 65, giving the sequence a cinematic width that contrasted the claustrophobia of the space. The wide frame let Vader dominate every inch of the screen whenever he entered a shot.

Lighting the Darkness

The most striking feature of the corridor scene is its lighting—or rather, its absence. Cinematographer Greig Fraser (later known for The Batman and Dune: Part Two) used minimal key light sources to ensure the only major illumination came from Vader’s lightsaber and the Rebels’ blaster fire.

Fraser and his gaffer team rigged practical LED panels into the walls that could pulse in sync with sound effects and visual cues. The red glow of the lightsaber was achieved using a real illuminated blade, not a post-production effect. This allowed light to spill naturally onto Vader’s armor and the surrounding smoke.

The production also filled the corridor with dense fog—using traditional dry-ice vapor—to give the light something to refract against. “It’s like painting with light,” Fraser explained. “The fog catches every flicker and makes the energy of the scene almost tactile.”

The combination of smoke, practical lighting, and limited visibility gave the scene its haunted-house aesthetic. It was cinematic chiaroscuro: light and shadow as instruments of terror.

Vader’s Physicality

Bringing Darth Vader to life required precision and reverence. The suit was recreated by Brian Muir’s team at Pinewood—Muir had sculpted the original helmet decades earlier.

The man inside the armor for Rogue One was Spencer Wilding, a 6’7” actor and stunt performer known for his creature work in Doctor Who and Guardians of the Galaxy. For certain sequences, Daniel Naprous, another tall stuntman, performed the more aggressive fight choreography.

Edwards instructed Wilding to move “like a shark—slow, deliberate, confident.” The key was restraint: Vader doesn’t run; he doesn’t dodge. He simply advances, absorbing everything in his path. This philosophy informed the blocking. Each Rebel’s death was timed to emphasize inevitability—no matter how fast they moved, Vader was faster.

For the saber choreography, the stunt team looked back to the original trilogy’s heavy, deliberate style, not the acrobatics of the prequels. Vader’s weapon is a broadsword, not a rapier. His strikes are fatal, not decorative.

Sound Design and Music

The auditory dimension of the corridor scene is as vital as its visuals. Supervising sound editor Matthew Wood (a Star Wars veteran) rebuilt Vader’s breathing track from the original analog recordings of Ben Burtt. The sound of the lightsaber ignition was also sourced from 1977 elements, slightly deepened to convey menace.

Each Rebel blaster shot was individually mixed to ricochet through the corridor, amplifying the sense of chaos. The sound team layered metallic impacts, screams, and mechanical hisses, creating an auditory overload that mirrors the Rebels’ panic.

Composer Michael Giacchino, who had just four weeks to write the Rogue One score, created an original cue titled “Hope.” The piece begins with throbbing bass tones under Vader’s rampage, then transitions to an ethereal swell as the plans reach the Tantive IV. Giacchino called it “a musical handoff”—from despair to hope, from Rogue One to A New Hope.

Directing the Fear

On set, Gareth Edwards treated the sequence almost like a short film. He used handheld cameras to follow the Rebels, putting the audience at eye level with their terror. The lens flares from blaster bolts were captured in-camera, not added in post.

Edwards recalled in interviews that they shot the scene with minimal rehearsal: “I wanted genuine panic. I told the actors, ‘When that door jams, you have one take to get those plans through.’”

He operated some of the handheld shots himself, crouched behind set pieces, capturing the raw immediacy of the soldiers’ perspective. The visual language switches from wide, god-like compositions (showing Vader’s dominance) to tight, chaotic close-ups (showing the Rebels’ desperation). The editing alternates between stillness and frenzy—Vader’s calm contrasted with the Rebels’ fear.

The idea was to give the corridor scene that continuity with A New Hope, while still giving audiences the experience of a modern film, especially as the scene would be naturally compared with Vader’s introduction in A New Hope, when he boards Princess Leia’s ship.

“We tried to do a mixture of the very classical, very considered camera moves, you know, that you saw in the original trilogy,” Edwards explained, “and then sort of more frenetic, handheld, sort of embedded photography and this sequence, I really like the way it sort of inter-cuts both styles and I think that contrast is what keeps it energetic.”

The climax, when the plans are finally passed through the door, was shot with high-speed cameras to elongate the moment. Time seems to slow as Vader reaches forward, his saber slicing through the air just as the door slams shut.

Post-Production and Visual Effects

While much of the corridor scene relied on practical effects, Industrial Light & Magic (ILM) enhanced certain details: blaster bolts, sparks, and the subtle distortion around the lightsaber blade.

The compositing team ensured the energy from the saber cast accurate reflections on the surrounding metal. ILM also used volumetric lighting simulations to amplify the red haze without losing realism.

Digital clean-up was minimal—Edwards wanted the rough edges. “If something was a little off, that’s fine,” he said. “It feels more dangerous that way.”

Colorist David Cole finalized the look at Company 3, deepening the blacks and emphasizing red saturation. The contrast between darkness and red illumination became symbolic—the last glow of the Empire before the dawn of rebellion.

The Emotional Payoff

What makes the Vader corridor scene more than just an action set-piece is its emotional context. It’s not Vader’s story; it’s the Rebels’. Every second dramatizes what the Star Wars saga is fundamentally about: ordinary people facing impossible odds.

When the plans slip through the door and the Tantive IV escapes, the film transitions directly into the opening moments of A New Hope. The cut is seamless—a storytelling bridge across four decades.

Audiences erupted in applause. Critics compared the sequence to horror cinema and hailed it as one of the most satisfying moments in Star Wars history. It gave Darth Vader back his terror—a figure of myth, no longer a tragic antihero, but a living nightmare.