The Blueprint, The Con, and Production Chaos: How Bruce Geller and His Team Built Mission: Impossible

In front of the camera, the Mission: Impossible team was a well-oiled machine: a group of elite specialists working in perfect harmony under a cool, detached mastermind. Behind the scenes, the dynamic was shockingly similar—minus the harmony.

To create the defining spy procedural of the 1960s, creator Bruce Geller had to become the ultimate Jim Phelps. He couldn’t do it alone, so he assembled a crack team of specialists, each brought in for a specific skill. But they didn’t invent the formula from scratch; they synthesized the best elements from cinema, literature, and real-world cons to create something entirely new.

Assembling the Team

Geller knew that to distinguish his show from the solo-hero antics of James Bond, he needed a complex, layered approach. He recruited William Read Woodfield for the con, Laurence Heath for the fix, Lalo Schifrin for the rhythm, and director Bernard Kowalski for the look.

Together, these men formed a real-life “Impossible Missions Force.” They didn’t just write scripts; they engineered a machine. And to build it, they pulled blueprints from four distinct sources to create a unique hybrid.

Influence #1: The Mechanics (Topkapi)

If Bruce Geller built the body of the car, he adapted the chassis from the cinema. He took his primary inspiration from heist films, especially the 1964 Jules Dassin film Topkapi.

In this film, director Jules Dassin recreated the tense, silent heist technique he had pioneered in his earlier noir classic Rififi (1955). Topkapi depicts a theft from the Sultan’s treasury in Istanbul, but one sequence in particular provided the DNA for Mission: Impossible.

The Original Ethan Hunt: This silent suspension scene from ‘Topkapi’ (1964) was the direct inspiration for the franchise’s most famous stunt.

For nearly thirty minutes, the film abandons dialogue entirely to focus on a single, agonizingly difficult physical task. To steal an emerald-encrusted dagger, the thieves must bypass a floor rigged with pressure sensors so sensitive that a single footstep will trigger the alarm—effectively creating a cinematic version of the childhood game “the floor is lava.” The solution is as elegant as it is perilous: the thief is suspended from the ceiling by a rope, lowered inch by inch toward the display case. The tension in the scene hinges entirely on the thief’s physical control—specifically, the terrifying possibility that a single bead of sweat might fall from his brow, hit the sensors below, and trigger the alarm.

(Decades later, in the 1996 Mission: Impossible feature film, director Brian De Palma paid direct homage to this scene when Tom Cruise’s Ethan Hunt is lowered into the CIA vault. The wire suspension and the iconic moment where Cruise catches a drop of sweat in his hand were a high-budget resurrection of the very sequence that sparked Geller’s imagination.)

Influence #2: The Look (The Ipcress File)

While Topkapi provided the narrative structure, the show’s distinct visual style came from Geller’s “creative soulmate,” director Bernard L. Kowalski.

Kowalski was not just a hired gun; he and Geller were old war buddies. They had previously worked together as producers on the final season of the western Rawhide, where they attempted to deconstruct the “cowboy myth” with dark, psychological storytelling. The network hated it, and both men were fired in the infamous “Christmas Eve Massacre” at CBS. When Geller got the green light for Mission: Impossible, he immediately called Kowalski to help him finish the revolution they had started.

Kowalski directed the pilot and established the show’s visual vocabulary. He had seen the 1965 British spy film The Ipcress File and was so impressed that he explicitly requested a similar “mood and urgency” be emulated for Mission: Impossible.

Unlike the polished, wide-open shots of James Bond, The Ipcress File was claustrophobic and disorienting. Kowalski applied this to the IMF, utilizing severe Dutch angles (tilting the camera so the horizon line is not level) to create a subconscious sense of unease. He also constantly placed objects in the extreme foreground—shooting scenes through lampshades, from behind bookshelves, or through the gaps in a door frame. This technique made the camera feel less like an observer and more like a spy hiding in the corner, perfectly matching Geller’s paranoid tone.

Influence #3: The Plot (The Big Con)

With the look and mechanics established, the narrative engine was installed by Geller’s “specialists” in the writers’ room—specifically the partnership of William Read Woodfield and Allan Balter.

In the earliest episodes, the missions were often simple “snatch and grab” operations. It was Woodfield—a real-life devotee of magic and trickery—who pushed the show toward psychological warfare. He was obsessed with David Maurer’s 1940 non-fiction book The Big Con: The Story of the Confidence Man.

Maurer’s book detailed the complex “long cons” used by grifters, such as “The Wire” (delaying horse race results) or “The Rag” (insider stock trading). Woodfield and Balter realized the IMF shouldn’t just be thieves; they should be con artists.

Woodfield introduced the concept of the “Big Store”—a classic con-artist strategy where an entire fake environment is constructed to deceive a single “mark”. This fundamental shift meant that the team spent their time engineering fake elevator shafts and projecting fabricated realities rather than engaging in gunfights.

The Turning Point: Episode 6 (“Odds on Evil”)

This episode served as the “proof of concept” for the show’s move toward psychological warfare. Targeting a corrupt, gambling-addicted prince, the team’s methodology focused on Induced Neurosis:

The Gaslight: Instead of stealing money, they used technology to manipulate a roulette wheel, specifically to destroy the prince’s belief in his own luck and decision-making.

Psychological Breakdown: By meticulously controlling his environment, the team forced the target into a state where he could no longer trust his own senses.

The Result: The target was not defeated by force; he was defeated by his own fractured psyche, eventually committing treason because the IMF had made it seem like his only logical escape.

The IMF Methodology: Psychological Dismantling

Through the scripts of the Geller era, a consistent set of tactical “moves” emerged that replaced traditional action tropes:

Sensory Manipulation: The team frequently drugged targets to wake them up in “transformed” environments—such as making a mark believe he was in a foreign prison or years in the future—to shatter his psychological defenses.

The Time Squeeze: Writers often manufactured a fake “ticking clock”—a simulated plague outbreak or a police raid—to force the target into a state of panic where they would make irrational, desperate mistakes.

The Mirror Effect: The IMF rarely “conquered” a villain directly; instead, they reflected the villain’s own greed or paranoia back at them. The goal was to manipulate the target into a position where they were eventually destroyed by their own allies or their own vices.

The Rejection of Force: Geller notoriously insisted that the agents rarely use firearms. He believed that pulling a gun represented a failure of the intellect; the ultimate victory was leaving the target alive and utterly broken, without them ever realizing they had been played.

Influence #4: The Legal Dispute (21 Beacon Street)

While the plots came from The Big Con, the structure faced a legal challenge from an earlier source. The producers were sued for plagiarism by the creators of a short-lived NBC series called 21 Beacon Street (1959).

21 Beacon Street featured a brilliant private investigator named Dennis Chase who led a team of highly skilled specialists to solve cases using deception rather than force—a premise identical to the IMF. The pilot of 21 Beacon Street even featured a plot where the team used an elaborate con to take down a target.

The most damning evidence was Laurence Heath, the story editor for 21 Beacon Street, who later became a primary writer and producer for Mission: Impossible. Geller claimed he had never seen the earlier show, but the similarities were close enough that the suit was settled out of court. Laurence Heath joined the Mission: Impossible production almost immediately, writing the Season 1 episode “Wheels” (Episode 7, aired October 29, 1966). He remained on staff for years, becoming the “fixer” who could handle the darker, more complex episodes that Geller struggled with, effectively bridging the two shows.

The “Blank Slate” Philosophy

With the visuals from Topkapi and The Ipcress File locked in, Geller instituted his own rigid philosophy to control the mixture: Minimal Character Development.

To Geller, the IMF was not a family; it was a machine. He believed that if the audience knew too much about the agents’ private lives—their lovers, their traumas, their favorite foods—it would break the spell. He wanted his characters to be blank slates. In his view, to be a convincing undercover operative, one had to be devoid of a recognizable self.

This caused endless friction. Writers would constantly try to sneak in “character moments” to give the actors something to chew on, and Geller would ruthlessly cut them. In the seven-year run of the original series, the agents were almost never seen off-duty.

A Turbulent Cast: The Theory in Practice

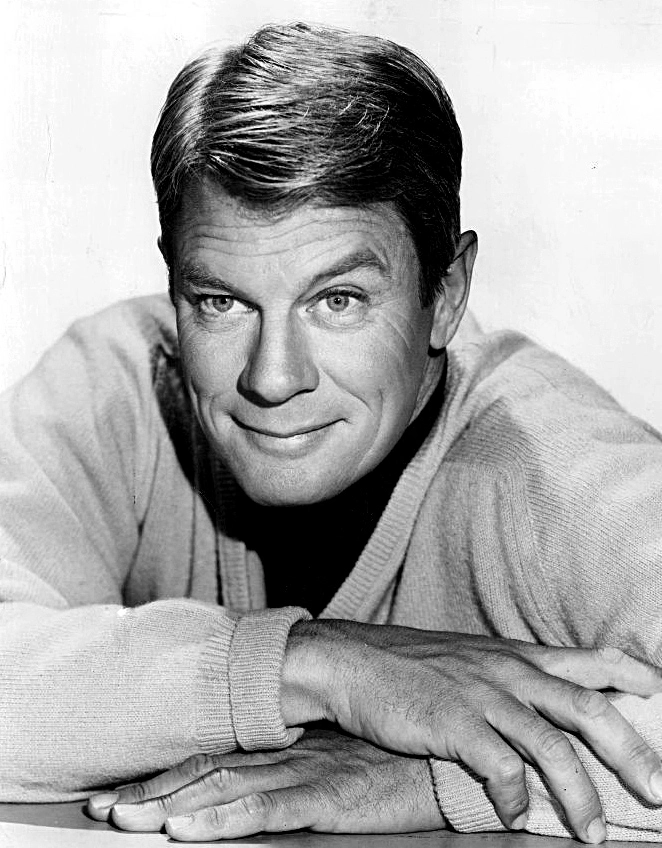

Geller’s “machine” philosophy was eventually tested by the realities of production. The show’s original lead, Steven Hill (Dan Briggs), was an Orthodox Jew whose strict observance of the Sabbath made the rigorous shooting schedule nearly impossible.

Hill had made it clear he could not work from Friday evening until Saturday night. Geller initially agreed to these terms, but the show’s grueling production schedule soon made this untenable. Hill also developed a reputation for being “difficult,” clashing with directors and refusing to perform certain physical actions (like climbing ladders or crawling through tunnels).

When Paramount Pictures purchased Desilu Studios from Lucille Ball, production continued under new ownership, but the patience for Hill’s restrictions ran out. His conflicts led to his departure after just one season. He was simply replaced by Peter Graves as Jim Phelps.

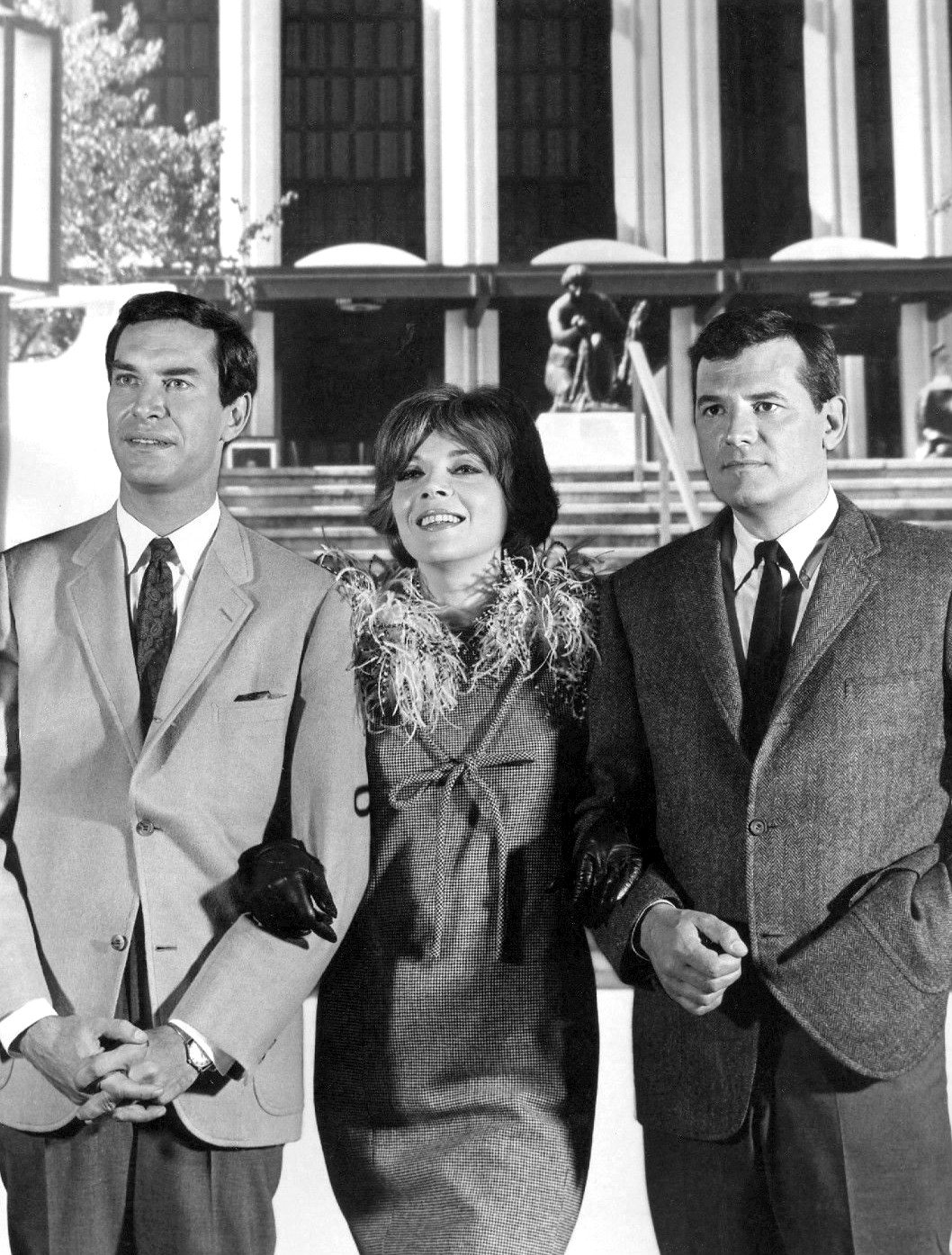

The turbulence didn’t end there. Following Season 3, the show lost two of its Emmy-winning stars, Martin Landau (Rollin Hand) and Barbara Bain (Cinnamon Carter), due to salary disputes. This proved Geller’s theory correct: the show simply slotted in new parts. Leonard Nimoy, fresh from Star Trek, replaced Landau as “The Great Paris,” and Lesley Ann Warren eventually joined as the new female lead. Because Geller had designed the show as a mechanism rather than a character study, the machine kept running.

The Decline and Demise: Budget Cuts and Culture Shifts

While the show survived cast changes, it could not survive the changing landscape of 1970s television.

After Season 5, Paramount executives actually wanted to cancel the show to cash in on syndication profits. However, a surprising ratings bump convinced CBS to order new seasons—but with a catch. The studio imposed draconian budget cuts.

The Skeleton Crew: The core cast was trimmed to just four members.

The Look: The expensive location shoots and “exotic” international flavor were replaced by stock footage. Later episodes were often filmed in the same recycled warehouse interiors to save money.

As a result, the series transformed from a cutting-edge international thriller into a more routine, localized police procedural.

The final blow came in 1973. A bitter dispute between Paramount President Frank Yablans and CBS President Robert Wood strained relations between the companies. With ratings already falling—the seventh season ranked at a dismal #57—CBS moved the show to the “death slot” of Friday nights at 8:00 PM.

Plans for an eighth season, which writers had already begun outlining, were scrubbed. The final episode aired on March 30, 1973.

While the corporate infighting killed the show, the end of the spy craze played a significant role. By 1973, the cultural mood had shifted. The Watergate scandal was dominating headlines, and the public’s trust in government institutions—specifically “covert ops”—had evaporated. The idea of a government agency that operated outside the law to topple foreign regimes was no longer “cool” fantasy; it was an uncomfortable reality. Films like The Parallax View (1974) and Three Days of the Condor (1975) would soon portray spies not as heroes, but as threats to democracy. The IMF had simply outlived its era.

Mission: Impossible 2.0: A Short-Lived Revival

Bruce Geller died tragically on May 21, 1978, when the Cessna Skymaster he was piloting crashed near Santa Barbara, California. However, his “machine” proved durable enough to function without him.

In 1988, the franchise was resurrected due to a labor dispute. During the 1988 Writers Guild of America strike, ABC needed content that didn’t require new scripts. They realized they could simply remake the original Mission: Impossible episodes using the 1966 scripts.

Production was moved entirely to Australia—shooting the first season in Queensland and the second in Melbourne. This decision was purely economic, reducing the show’s shooting budget by roughly 20% compared to Los Angeles. However, it gave the series a slightly surreal, generic look as Australian streets tried to double for Paris and Eastern Europe.

The revival forged a fascinating link to the past. Peter Graves returned as Jim Phelps, and in a meta-casting coup, the new tech expert Grant Collier was played by Phil Morris, the real-life son of original cast member Greg Morris (Barney Collier).

The team was rounded out by Thaao Penghlis as Nicholas Black and Tony Hamilton as Max Harte. The female lead, however, saw a dramatic shake-up. Terry Markwell, who played Casey Randall, was unhappy with her role and limited screen time. She exited the series after Episode 12, but the writers gave her a departure that shattered the show’s “invincibility” myth. In a shocking twist, her character was captured and executed during a mission—the first time a core IMF agent was ever killed in action. She was immediately replaced by Jane Badler as Shannon Reed.

Ultimately, it was poor strategy, not poor storytelling, that killed the revival. Season 1 ratings were surprisingly high, proving there was still a hunger for the classic format, which led to a renewal. However, the network blundered by moving the show to Thursday nights for Season 2, where it faced stiff competition and ratings tanked. Mid-season, executives tried to salvage their miscalculated decision by restoring the show to its original Saturday night slot, but the damage had been done. Viewers did not return, leading to the show’s cancellation after just two seasons.

The Only “True” Mission: Impossible Film

Ultimately, the franchise came full circle in 1996 with the first Mission: Impossible feature film. Director Brian De Palma paid the ultimate homage to the original “Geller team” by synthesizing their key contributions. He recreated the famous “suspended from the ceiling” heist from Topkapi (the Mechanics), and he utilized severe Dutch angles throughout the film (the Look), reviving the claustrophobic paranoia established by Kowalski thirty years prior.

However, despite being the only film in the franchise that successfully captured the specific flavor and tension of the original series, it committed a cardinal sin that alienated the original cast. In a shocking twist, the film revealed that Jim Phelps—the unwavering moral center of the IMF for decades—was actually the villain.

The decision was a meta-narrative execution; by turning Phelps into a traitor, the film literally killed off the old television format to birth the new blockbuster franchise. The intricate team dynamics—the heart of Geller’s vision—were sidelined in favor of making its superstar lead, Tom Cruise, the singular hero in the “American Bond” mold.

This transformation deepened as the sequels progressed. While Ethan Hunt eventually built a loyal team around him, the dynamic had fundamentally shifted from Geller’s cold, professional “machine” to a warm, sentimental “family.” In the films, Hunt is defined by his intense emotional attachments, often risking global catastrophe to save a single team member—the antithesis of the original IMF, where agents were interchangeable assets to be disavowed at the first sign of failure.

For decades, this new formula proved to be a mega-hit. But even the biggest stars eventually fade. The last two entries suffered at the box office, criticized for becoming modular collections of stunts rather than cohesive stories. The irony remains that the franchise, having spent years running away from its roots to chase the solo hero archetype, ultimately ended up as a recreation of the very Bond-style action Geller had originally sought to subvert.