Calculated Chaos: The Mechanics and Practical Stunts of the Live and Let Die Boat Chase

In the history of cinematic aquatic action, the boat chase in Live and Let Die (1973) stands as a massive mechanical upgrade to the daylight speedboat template established a decade earlier in From Russia with Love (1963). While the earlier sequence was a landmark spectacle of flame and fiery stuntwork that redefined how speedboats were filmed to show fast movement, the 1973 pursuit pushed these boundaries even further.

Director Guy Hamilton significantly increased the complexity by incorporating the aquatic pursuit with a simultaneous car chase involving police cruisers along the parallel bayou levees. It was a sequence defined by high-speed physical obstacles—skidding across lawns, jumping over roads, and punching through blockades—culminating in a fiery conclusion that saw Bond once again use his ingenuity to devise an escape. This marked the franchise’s full transition into the era of the high-concept, practical “stunt-piece” blockbuster.

The Creative Vacuum: A Script Born in the Swamp

The genesis of the Live and Let Die boat chase was famously disorganized, born from a creative vacuum that illustrates the “wing-it” philosophy of 1970s blockbuster production. For a significant portion of pre-production, the script was essentially a placeholder. In his memoir, My Life as a Mankiewicz, screenwriter Tom Mankiewicz recalled that for months, the screenplay simply read: “And then follows the most amazing boat chase you ever saw.”

This was not merely a result of writer’s block, but a strategic hesitation. The production knew they wanted a boat chase, but the topography of the Louisiana bayous was so unpredictable that committing to specific action beats on paper felt premature. It wasn’t until ten days before principal photography was scheduled to begin that United Artists formally requested that the sequence be scripted.

This prompted Guy Hamilton to send Mankiewicz to his hotel room in New Orleans with a strict deadline: he was not to emerge until the “most amazing boat chase” was a reality. Mankiewicz spent the next 48 hours crafting the logic of the chase, integrating the comedic presence of Sheriff J.W. Pepper and the logistical reality of the bayou’s “interlocking” water and land paths.

Source: MovieStillsDB.com

The Twenty-Four Day Marathon: A Baptism of Fire

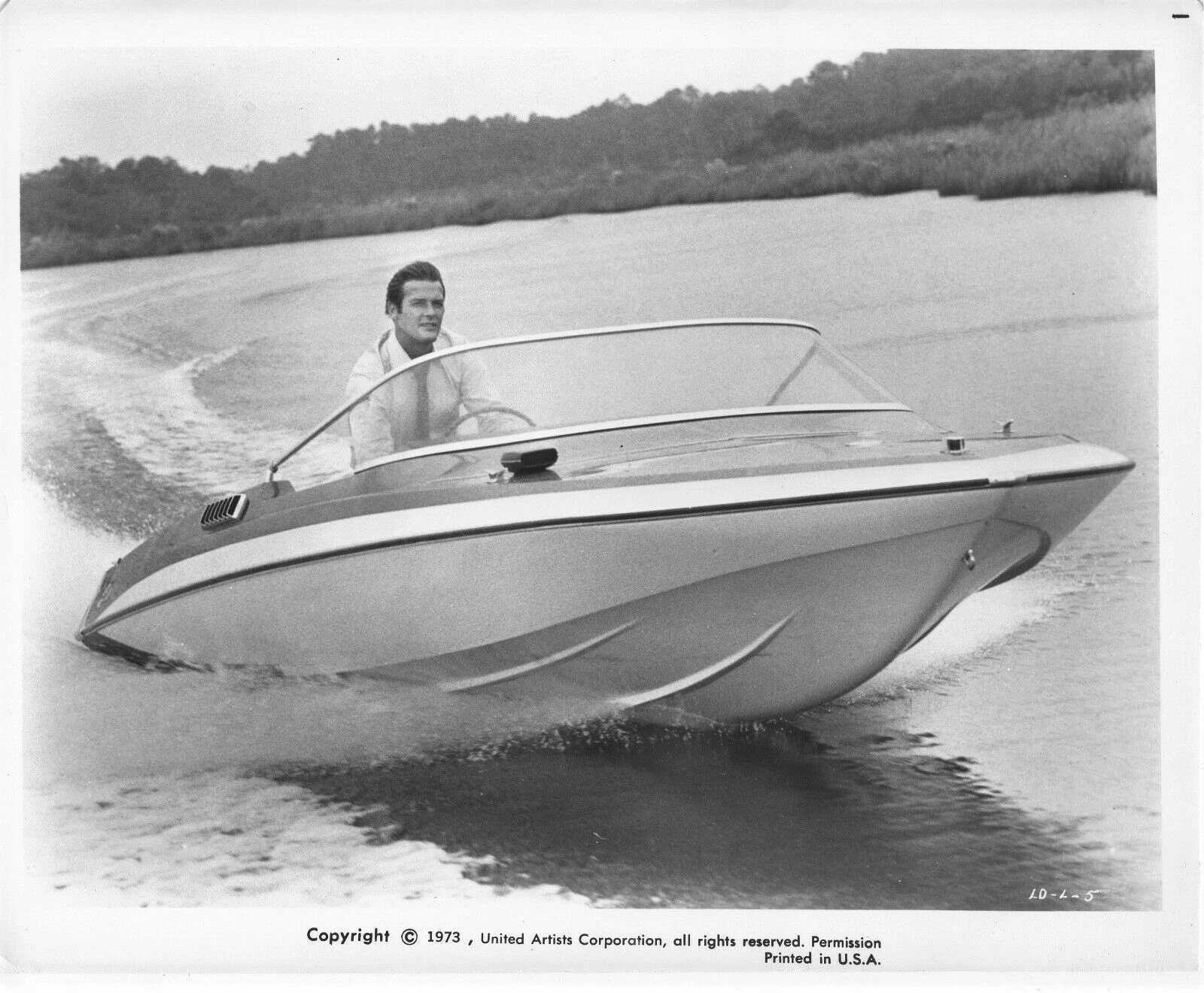

The production schedule for Live and Let Die was as unconventional as its script. Eschewing the traditional “dialogue-first” approach, principal photography for Roger Moore’s debut began with the roar of a two-stroke engine. The boat chase was the very first sequence filmed, starting on October 13, 1972.

The shoot was a grueling, twenty-four-day marathon that took the crew deep into the humid, mosquito-infested wetlands of Slidell and the Irish Bayou. This period was marked by the constant noise of the high-performance outboards and the logistical nightmare of moving heavy camera equipment across unstable marshes.

In his autobiography, My Word is My Bond, Roger Moore recalled being thrown straight into the deep end, positioned behind the wheel of a Glastron GT-150 capable of speeds up to 75 mph. It was fourteen days into the shoot before Moore even uttered his first line of dialogue as James Bond. For the first two weeks of his tenure, the world’s most famous secret agent was essentially a stunt driver.

For his first two weeks as 007, Roger Moore was effectively a stunt driver, piloting the GT-150 through the narrow Irish Bayou channels. (Source: MovieStillsDB.com)

This “silent” period was nearly Moore’s last. During high-speed training, the steering on Moore’s Glastron jammed. The boat veered sharply off course, crashing into a massive oak tree. Moore was thrown forward, resulting in a chipped tooth and a debilitating knee injury. As Moore noted in his recollections, he continued to film despite the pain, performing his own driving while his knee was heavily bandaged and hidden under his wardrobe.

Meddings, Lamont, and the Dual Pursuit

The technical success of the sequence rested on the shoulders of Peter Lamont and Derek Meddings. When regular special effects wizard John Stears was unavailable, Syd Cain enlisted Meddings, a pioneer of miniature effects who had spent years perfecting Gerry Anderson’s Thunderbirds.

Lamont detailed the dual car-boat choreography in his book, The Man with the Golden Eye, explaining that Meddings was tasked with supervising a simultaneous pursuit where the speed of the boats in the channel had to be perfectly synchronized with the speed of the Plymouth Furys on the asphalt levees.

To capture this, the camera department faced extreme physical risks. Camera operator Bob Kindred later described how he and Director Guy Hamilton often had themselves literally tied to the front of chase boats, traveling at speeds exceeding 60 mph to secure steady close-up POV shots. The technical setup utilized Panavision Super PSR R-200 and Arriflex 35 IIC units, which had to be heavily secured to withstand the “porpoising” (heavy bouncing) of the boats in the choppy bayou water.

The Engineering of the Glastron Fleet: Speed and Survival

The backbone of the sequence was a massive logistical partnership with the Glastron Boat Company. Peter Lamont oversaw the preparation of twenty-six boats for the sequence, a staggering number for a single action scene. Out of these twenty-six, five specific GT-150s were custom-fitted to double Bond’s primary vessel, known as the “Bond Five.” These were stripped down and rebuilt specifically for the rigors of high-impact stunt work.

Each boat was powered by an Evinrude Starflite 135hp outboard motor. These engines were pushed to their 75-mph limit, providing the “spectacle of speed” Hamilton demanded for the sequence. To prevent the brittle fiberglass hulls from shattering upon impact with the shore, Meddings and Lamont attached specialized sacrificial mahogany runners to the undersides, allowing the boats to “hydroplane” over the damp grass.

For high-velocity jumps over roads and levees, the SFX team constructed timber-framed ramps anchored into the swamp bed. Because a boat has no tires for lateral grip, the hulls were modified with two small black metal rails. Meddings remembers these rails acting like train wheels, slotting into guides on the wooden ramps to lock the boat into a perfectly straight trajectory during takeoff.

These ramps featured a central “relief” gap which allowed the propeller to continue spinning in clear air or shallow water while the hull’s rails took the weight on the outer tracks. Without this gap, the spinning propeller would have struck the wood at 70 mph, causing the boat to pole-vault uncontrollably. To further ensure the boats didn’t roll or torque mid-air, the steering and the single bucket seat were moved to the exact longitudinal center of the hull.

The Jet-Drive Pursuit: Adam and the “Billy Bob” Boat

One of the most technically distinct vessels in the fleet was the Glastron-Carlson CV-21, driven in the film by the villainous henchman Adam. Known on-set as the “Billy Bob” boat, the CV-21 was the heavyweight of the pursuit.

Unlike Bond’s outboard GT-150, Adam’s CV-21 was a jet boat powered by a massive 455 cubic inch Oldsmobile V8 engine paired with a Berkeley jet unit. Because the boat relied on an internal jet impeller rather than an external propeller, it was the ideal vehicle for the sequence’s high-speed land jumps. Adam’s boat could launch over asphalt and skid across levees without the mechanical “pole-vaulting” risk inherent in outboard engines.

While the jet drive protected the engine, it offered zero directional control once the hull left the water. Stunt drivers had to rely on sheer momentum to guide the heavy V8-powered hull across the Louisiana grass, often battling the boat’s tendency to spin uncontrollably.

Outboard vs. Jet-Drive: The Technical Divide

In a clever piece of editing, the audience often sees Bond and Adam performing similar maneuvers, but the technical reality was split between two engineering philosophies. In his DVD commentary for the Ultimate Edition, Peter Lamont explained the necessity of using different boats for different terrains.

The GT-150 faced a potential “catastrophic stop” on every land jump. It relied entirely on the “Relief Channel” ramps to ensure the spinning propeller never touched asphalt or wood. It was chosen for the “flying” stunts because its lighter weight allowed for the record-breaking trajectory. In contrast, Adam’s jet boat functioned like a giant jet ski, capable of “hopping” across a road or levee without a specialized relief ramp because the bottom of the hull was nearly flush. However, the heavy V8 engine made it a “lawn-dart” in the air, making it too rear-heavy for the 120-foot jump attempt.

After the GT-150 is “shot” and abandoned in the swamp, Bond actually steals a white and gold CV-19 Jet Boat. This allowed the production to film more aggressive land-skids in the latter half of the chase, as the jet boat was far more durable for “off-road” use than the delicate outboard GT-150.

Practical Stunts:

The “Car-Boat” and Miller’s Bridge

In his book, Not Forgetting James Bond, Art Director Syd Cain detailed the “hands-on” nature of the stunts, which would be deemed impossible by modern safety standards. One of the most iconic visual gags involves a pursuing speedboat launching over a bank and ploughing directly into Sheriff J.W. Pepper’s parked police vehicle. This was a 100% practical stunt; Meddings’ team had to physically weld a boat hull to the roof of a police cruiser to create the wreckage.

At Miller’s Bridge in Phoenix, Louisiana, the authorities attempt to end the pursuit with a floating “riverblock.” The crew tied a series of small, decommissioned boats together across the channel. To ensure Bond’s boat could punch through without flipping, the SFX team used chainsaws to “pre-score” and weaken the hulls of the stationary boats before impact.

The “car-boat” scene. The production destroyed 17 of the 26 boats ordered for the sequence.

The Physics of the 120-Foot Jump: The Tulane Equations

The jump over Crawdad Bridge remains the technical crown jewel of the film. Stuntman Jerry Comeaux spent six weeks preparing for this single leap, yet initial practice jumps were plagued by crashes. To ensure the jump was successful—and that Comeaux survived—the production consulted with the Mathematics Department at Tulane University.

The physics were daunting: because a speedboat is a hollow shell, it acts as an airfoil at high speeds. If the nose lifted too much, the air pressure under the hull would flip the boat backward. Tulane’s professors calculated the exact angle for the ramp and the precise speed—72 mph—required to clear the road and the cars parked beneath the bridge. The stakes were absolute; if the math was off by even 2-3 mph, the boat would have likely cartwheeled into the bridge pilings. A perfect take was achieved on the third attempt, recording a crew-measured distance of 120 feet from take-off to re-entry.

Stuntman Jerry Comeaux hit the ramp at exactly 72 mph to achieve this world-record jump. The angle was calculated by Tulane University mathematicians to prevent the boat from flipping backward. (Image Source: MovieStillsDB.com)

The Esther Williams Influence and the Producer’s Conflict

As the sequence grew in scope, Director Guy Hamilton originally envisioned an “aqua-musical” detour inspired by Esther Williams, the 1940s MGM superstar. Hamilton’s vision would have seen the chase detour through a public “Southern Water Show” in front of a cheering audience.

In the centerpiece of the stunt, Bond would swerve through a “triangle of men on skis.” This human pyramid featured the men carrying pretty girls on their shoulders, who held little banners. Bond’s boat was intended to pass by the formation without disturbing a single skier, while a pursuing enemy boat would cause the entire pyramid to collapse.

However, producer Cubby Broccoli wasn’t happy telling co-producer Harry Saltzman: “This f*ing boat chase just goes on and on.” Broccoli put a hard stop to any further action, killing the Esther Williams sequence and a planned Slidell boatyard finale that would have featured Bond using a decommissioned ferry as a massive ramp.

Adam’s Death and Destruction: The Condensed Climax

Because of Broccoli’s intervention, the planned “Ferry Jump” finale was significantly condensed into the Slidell Harbor conclusion seen in the final film. Second Unit Director John Glen, in his book For My Eyes Only, noted the practical reality of this final beat.

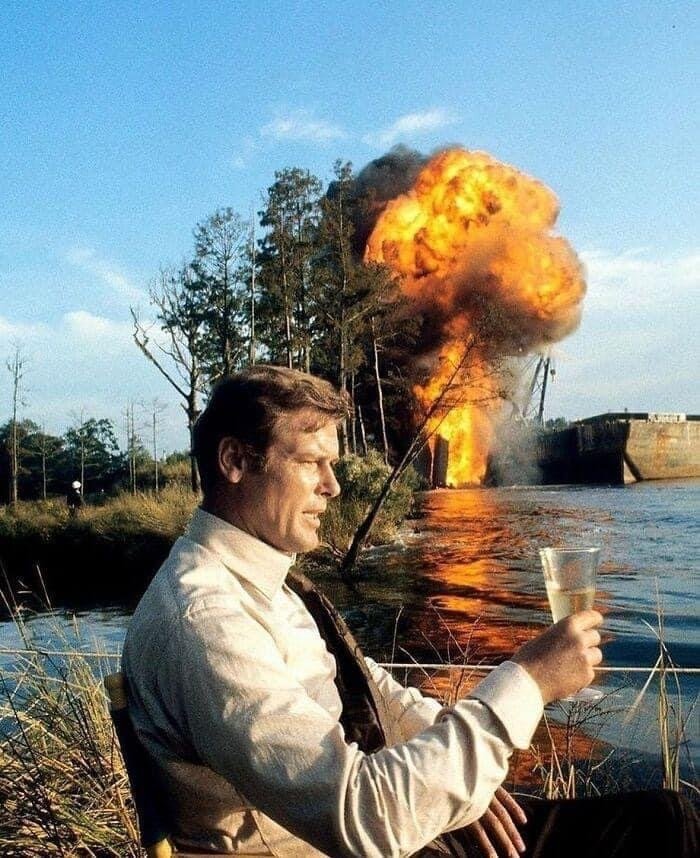

Rather than a spectacular leap, the pursuit ends with Adam’s jet-powered CV-21 ploughing into the wreckage of a decommissioned ferry and exploding. The collision was a 100% practical effect; the speed of the jet boat meant that when it struck the ferry’s rusted metal hull, the impact was severe. The production used carefully placed explosives to ensure the Oldsmobile engine’s fuel load “ignited” on cue, providing the fiery punctuation Broccoli demanded.

Roger Moore calmly enjoying a drink while an explosion signaling the destruction of Adam’s boat detonates in the background (Source: MovieStillsDB.com)

Mechanical Roar: The Sound Design of the Pursuit

The technical divide between the vessels was further emphasized through a meticulous sound design strategy. Sound editors used audio to characterize the chase as a battle between Bond’s clinical efficiency and the villains’ raw, overwhelming power. For Bond’s GT-150, the sound team highlighted the high-pitched, metallic “zing” of the Evinrude Starflite, mixed to emphasize speed and high-RPM agility.

In contrast, Adam’s “Billy Bob” CV-21 was given a much deeper, more guttural audio profile. By recording the open-header exhaust of the 455 Oldsmobile V8, the sound team created a low-frequency “thrum.” As George Martin noted in his book All You Need Is Ears, this was intentionally mixed to sound more menacing, suggesting a blunt-force instrument chasing down Bond’s sophisticated vessel.

The Blueprint for the Stunt-Piece Blockbuster

The sequence’s legacy is defined by its Practical Standard. It demonstrated that the sight of a real boat flying 120 feet through the air provided a visceral thrill that miniatures or rear-projection simply could not match. By integrating a car pursuit into the aquatic action and utilizing rigorous mathematical planning, the production established a blueprint for the “stunt-piece” blockbuster that would influence directors for decades.