Octopussy’s Flight Risk: The Full Story Behind the Acrostar BD-5J Microjet And The Coolest James Bond Opener Ever

After being dropped from Moonraker, the Acrostar BD-5J microjet made a big impression in Octopussy. Learn how stunt pilot J.W. “Corkey” Fornof, director John Glen, and special effects supervisor John Richardson used an”undramatic” television commercial as inspiration for one of James Bond’s most thrilling pre-title sequences.

Almost every James Bond film begins with its trademark pre-title sequence, a “mini-movie” that typically sees 007 perform an incredible stunt to get out of an impossible situation, just before the opening credits roll. These sequences rank as some of the most iconic moments in cinema, and the problem facing the Bond producers on each new film is how to top the previous one.

Nevertheless, over the course of 25 films, a few pre-title sequences stand above the rest, and one of the best is the pulse-pounding opening to Octopussy. Immediately, all Bond fans know this is the pre-title sequence that features the world’s smallest jet, the Acrostar BD-5J (or Bede jet), evading a heat-seeking missile by flying into an aircraft hangar and emerging out the other side, just moments before the missile blows the hangar sky-high. It’s the kind of signature stunt that pre-title sequences in the Roger Moore era were known for, like the ski-BASE jump off a mountain in The Spy Who Loved Me and freefalling without a parachute in Moonraker. There’s a certain panache that Moore’s Bond has and it is echoed in his pre-title sequences. It also helps that John Glen, the director of three of Moore’s Bond films, had also been the second unit director on both The Spy Who Loved Me and Moonraker leading the team that filmed the stunning pre-title sequences in both those films. By Octopussy, Glen was at the top of his game as an action director and would send Bond on his all-time high.

The Unused Aerial Sequence In Moonraker

Many Bond action sequences are written around Bond’s signature vehicle or stunt, and this sequence is no different. Director John Glen brainstormed ideas for the 13th Bond film’s pre-title sequence. But it wasn’t until production designer Peter Lamont asked Glen if he could do something with the aircraft props stored at Pinewood Studios, that the idea for using an Acrostar BD-5J in Octopussy first emerged. The props were three shells of the Acrostar microjet built for a planned aerial sequence in Moonraker featuring two of these mini jets: one flown by James Bond (Roger Moore) and the other by Holly Goodhead (Lois Chiles). Not much is known about the sequence except that the two secret agents would fly the jets over an undisclosed South American river. The sequence would have, most likely, engaged the two allies in aerial combat, but it was scrapped because the river bed dried up.

The Acrostar had been sidelined for a seemingly inconsequential reason. Director John Glen hoped the pilot, J. W. ‘Corkey’ Fornof, would still be interested in doubling Bond in the plane four years on. Fornof had flown at airshows around the world, and performed in TV commercials, and movies. He had done almost everything in that plane except play James Bond. So it’s no surprise he accepted Glen’s offer.

The First Homebuilt Jet Plane

Fornof had built the plane himself and led the World’s First Civilian Jet Pilot Team, a three-man team formed by the US designer of the Acrostar BD-5J, Jim Bede. Fornof’s team helped legitimize Bede’s desire to supply an affordable, homebuilt, kitplane for the everyday person. It also helped erase controversies about the microjet’s predecessor, the propeller-driven BD-5, which, due to engine and design issues, resulted in 25 pilot fatalities out of only 200 pilots that ever flew the plane.

But this bad press didn’t blow back on the microjet. Not only is the Acrostar BD-5J the world’s smallest jet; but it was also the first homebuilt jet. The combination captured pilots’ imaginations immediately. Bede marketed it through ads, airshows, and articles in Popular Science. But unlike its predecessor, the microjet actually delivered, and it packed a punch. The plane’s single micro-turbo TRS jet engine sent the Acrostar microjet rocketing through the air at a top speed of 310 mph and climbing at a rate of 2,800 feet per minute to a maximum altitude of 30,000 feet.

It was a show-stopper. Light and maneuverable, the BD-5J weighs only 450 pounds, has a small wingspan of 17 feet, and a length of just 12 feet. Bullet-shaped with a fighter-like fuselage, the BD-5J is a sexy plane that looks like it belongs in a James Bond film.

Octopussy’s Opener Plays Like An Homage To The Microjet’s Pilot

When Fornof arrived in London, he met Glen and they discussed ideas for the sequence. Glen then wrote a cinematic sequence around those ideas. The sequence would showcase the size and maneuverability of the jet, which Bond uses to his advantage. As the world’s smallest jet, spies could conceal it in something small like a horse float.

The aerial sequence written by Glen works like a greatest hits package of Furnof’s stunts in airshows and commercials. Glen’s inclusion of the heat-seeking missile that Bond tries to shrug off, whether intentional or not, allowed Fornof to showcase the pitches, rolls, and other aerial stunts he performed at airshows. As a nice flourish, Bond (Fornof) performs a triumphant vertical barrel roll moments after narrowly escaping the missile and the exploding hangar. From the reaction of the people in the stands, it looks like they’re being treated to an impromptu airshow that is more interesting than the equestrian event they’ve come to watch. The sequence plays like a deliberate, self-referential in-joke to Fornof’s career, though the poor guy received no onscreen credit.

Bond’s emergency landing is also based on a landing Fornof had to make in real life. Even the main event, the flight through the hangar is a stunt Fornof had performed a year or so before for a Toshiba TV commercial in Japan. However, when Glen saw the commercial he was disappointed:

“…It showed him flying the speedy jet through an empty hangar. And it was gone in a flash. You can imagine he’s doing 300 miles an hour. And he goes through this hangar so fast, you know, was it, ‘Did I see that or didn’t I?”, sort of thing. It was so undramatic that they matted, very badly matted, some doors closing as the thing came in. So it was trying to make out it was a near escape. That’s what gave me the idea to use the doors closing in the scene for Octopussy.”

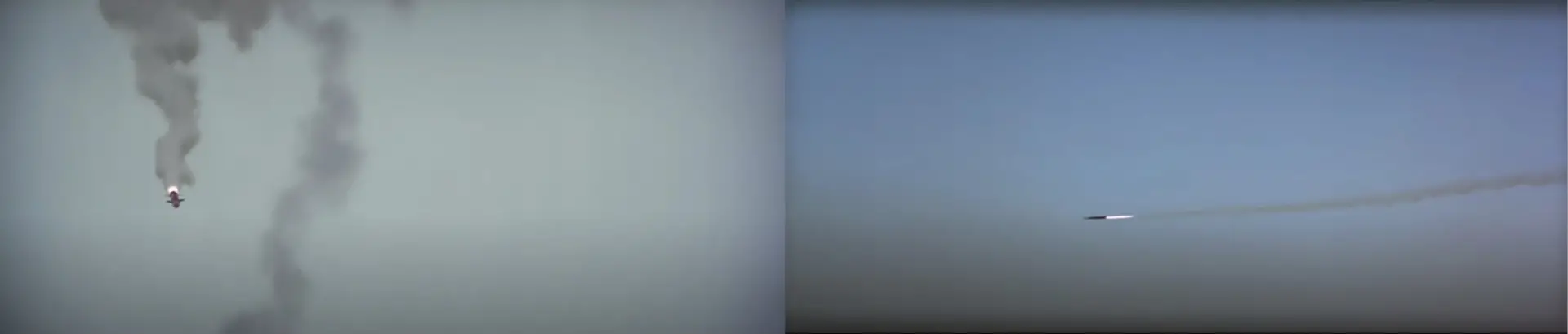

Old grainy footage of the Toshiba commercial still exists (below), which demonstrates why Glen was so unimpressed.

The Flight Through The Hangar Is No Stunt At All

Special Effects Supervisor John Richardson agreed with Glen when he saw the footage, recently describing it as “uncinematic” because it was over so quickly. Even more problematic was that Fornof said he could only perform the stunt if there were no actors or camera crew inside the hangar, one of the principal reasons the commercial lacked excitement. This didn’t work for Glen. He wanted people, and he wanted the plane to stay just a moment longer inside the hangar so the audience could actually see it. So he turned to Richardson, who decided to recreate the entire stunt with models and miniatures in order to have people safely running around inside and around the outside of the hangar. That’s right the jet you see flying into the hangar, through the hangar, and out the other side is a combination of miniatures and a full-scale model. There is not one shot of the real plane.

Both the Toshiba commercial and the stunt in Octopussy were filmed from completely different perspectives. In the commercial, the camera is placed at the hangar’s exit, showing the jet coming through the hangar directly towards the camera and flying over it. In Octopussy the camera is placed at the side of the hangar as it goes in one end and out the other.

This not only helped the Bond team make the stunt their own, but it also gave a more dramatic perspective and was practical for what Richardson and Glen wanted to achieve.

The Flight Into The Hangar Is An Optical Illusion

The scene was filmed at RAF Northolt airport at the end of August 1982, in and outside a real aircraft hangar. The Acrostar BD-5J that appears to fly into the aircraft hangar on-screen is a 1/3 scale miniature. This shot of a 1/3 scale miniature flying into a full-size hangar is actually an optical illusion using a foreground miniature.

A foreground miniature is a small model that is placed in front of a real-life structure to give the illusion of extending it, adding a feature that is not there, or covering up an existing architectural feature. Lined up correctly, the camera will record the miniature and the real structure as one seamless perspective-accurate building.

Richardson placed a 1/3 scale foreground miniature of the aircraft hangar’s sliding door very close to the camera. Lined up in the camera frame, the foreground miniature door matched up with the real hangar (as if it was part of the hangar itself) even though it was meters away. Then, the 1/3 scale Acrostar BD-5J was sent down on a wire rig, and “flew” in between the foreground miniature door and the real hangar. On-screen it looks like the miniature Acrostar is flying into the hangar. But it isn’t. A similar process was used for the missile flying into the hangar, and for the Acrostar BD-5J making its escape out the other end.

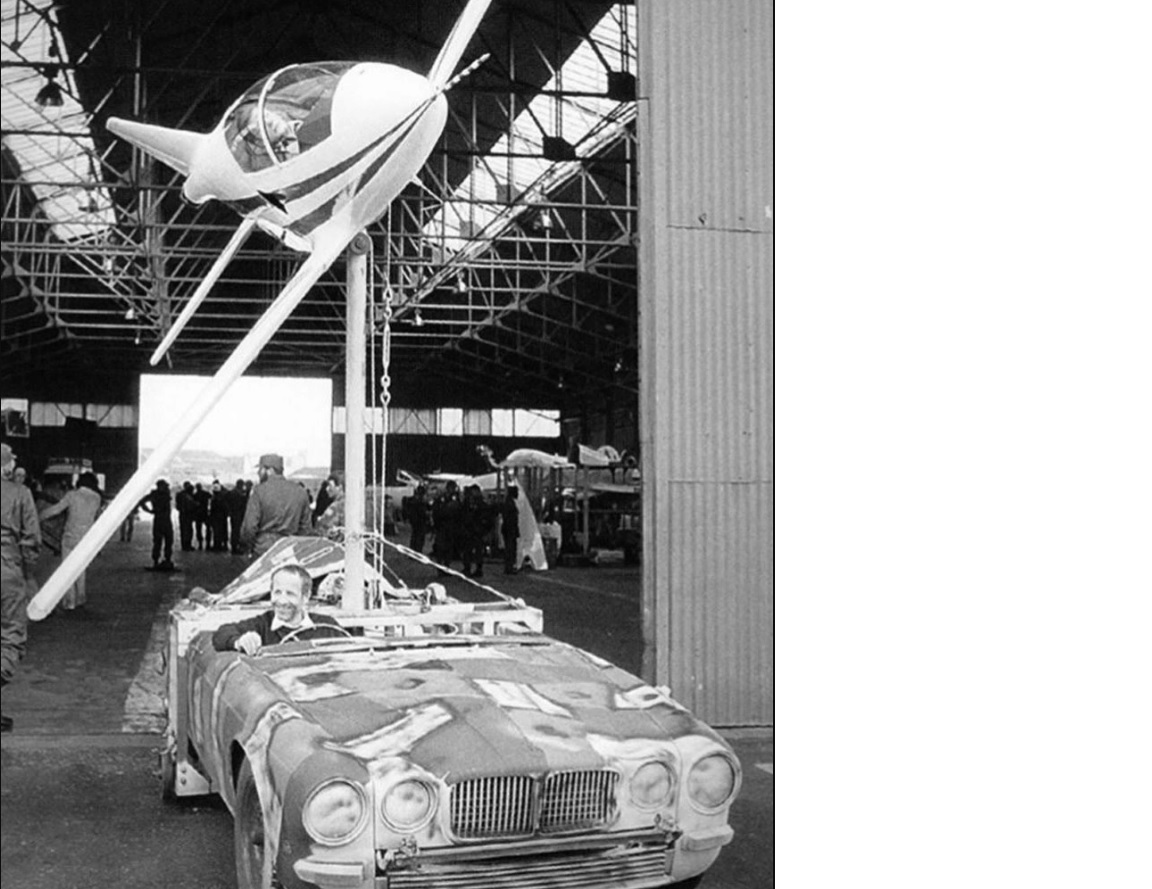

A Jet Plane Mounted On A Car

For the plane traveling inside the hangar, Richardson and his team built a full-size replica of the Bede jet. It was mounted to a 12 to 15-foot metal pole, which was stuck into the middle of a car, which Richardson drove from one end of the hangar to the other so the plane looked as if it was flying through the superstructure. The replica plane was mounted to the pole via a gimbal that allowed the Acrostar to roll on its side as Bond banked the plane to slip through the fast-closing hangar doors. The gimbal was controlled by an air hydraulic system in the car, and as an added bonus, the wing of the plane helped conceal the pole it was mounted on as it “flew” close to the camera.

Richardson’s team cut the top off a Jaguar to mount the pole. Painted gray camouflage, the Jaguar was further concealed from the camera by objects and people in the foreground. Richardson drove the contraption in a straight path through the hangar and out the fast-closing hangar doors at 75 mph. To ensure the car and mounted plane did not clip either door, stuntmen pushed the hangar doors along the sliding door track to stops which created a narrow gap just wide enough for the car and plane to pass through safely.

The real danger for Richardson occurred once he exited the hangar and the car’s brakes failed.

“When he drove out of the hangar,” recalled Glen,” the linkage to the accelerator suddenly broke and it suddenly went flat out and he was suddenly driving this contraption with an airplane on the top, driving it around with parked aircraft that belonged to the RAF and narrowly missing them. That was quite a moment.”

Richardson is an old-school model and miniatures expert. Now in his 70s, he’s worried the art form is dying with the film industry’s reliance on CGI. This over-reliance on CGI, he warns, is causing a lack of ingenuity in current VFX teams. However, the sequence still relied more on special effects than any previous pre-title sequence. In fact, while Fornof does indeed perform stunts in his Acrostar, the sequence is a cleverly edited together sequence that continually moves back and forth from the real plane, to miniatures, and to full-scale models.

In each part of the sequence, a specific aircraft and missile is used to fulfill a specific technical objective that Richardson and his crew needed to achieve.

Here’s a breakdown of the various planes and missiles used:

The plane with fold-up wings seen exiting the horse float at the beginning of the sequence and stopping at the petrol station at the end is a modified BD-5J. The wings on Fornhof’s Acrostar BD-5J do not fold up or down.

Either this modified plane or another shell was used for the close-up shots of Moore in the cockpit.

A 1/3 scale remote control plane was used where the microjet appears in the same wide shot as the heat-seeking missile. This plane was powered by a propeller mounted to the nose. The propeller moved very fast so it didn’t show up in the footage and ruin the illusion the audience is watching a jet. At the time, jet engines were not available for model planes.

The heat-seeking missile in these shots is an approximately 1 meter-long miniature attached to the rear of the remote control plane via a nylon fishing line wound around a cotton bobbin from a sewing machine. The missile was attached to two little wire loops mounted to the underside of the remote control plane when it took off. When Richardson and his crew were ready to film the plane and missile, they rolled the plane over in midair, and the missile then unhooked and dropped off, and the nylon wire unwound from the cotton bobbin.

The nylon wire acted as a guide for the miniature missile to follow the remote control plane. But rather than being passively towed, the missile itself, had a radio transmitter in it, and a flare in the back. When the plane and missile were lined up, the crew hit a button and the flare lit up and both plane and missile were flown around.

If you watch the sequence, you can see the missile has a more disjointed flight than the tightly maneuvering plane. The missile head is more stable than the tail likely because the missile’s head is pulled by the wire attached to the plane, and the tail has more drag that is exacerbated by the flare. Every time the crew hit the button, they had only 10 to 15 seconds at a time to follow and film the remote control plane and missile in the sky with a long lens.

Richardson also built other models of the missile for different shots, including a missile fastened to a wire (below, left) which was shot on the backlot at Pinewood Studios. The missile moved down the wire towards the camera and is used in a variety of shots in the sequence, either by itself or rear-projected behind Roger Moore in the cockpit. Moore is filmed using his shoulder to knock the lightweight aircraft out of harm’s way as the missile zooms past.

Another missile was shot traveling through a tank of water while it emitted paint out its exhaust. The effect of the paint in water gave the look of a white, smoky trail.

Fornhof, of course, used his real Acrostar BD-5J for various rolls, pitches, and aerial stunts. He also performed the emergency landing at the end of the sequence. The real Acrostar is always the one solitary object in the frame. But it is given the illusion of being chased by a missile when edited together with the other footage of miniatures.

Both Richardson and Glen outdid themselves with this sequence. Glen wrote a mini-mission for Bond around the Acrostar BD-5J. It was actually only the second time, after Goldfinger, that Bond had been sent on a self-contained mission for the pre-title sequence. After Octopussy, the idea of starting the film off with a mini-mission would become more frequent in films like Goldeneye, Tomorrow Never Dies, Die Another Day, and Skyfall.

The buildup Glen created with Bond infiltrating the hangar to plant explosives, his capture, and ultimate escape in the jet is increased when Bond has to outrun the heat-seeking missile. Yet, he is still faced with a mission he has to complete. The ultimate payoff comes when Bond has to use his ingenuity to turn a failure into a success. He guides that heat-seeking missile right into the hangar to blow up the spy plane he was sent to destroy. Glen’s scripting of the sequence is pure genius and Bondian in the way 007 handles the situation. The sequence has more of a behind enemy lines, Cold War feel to it than any other Bond pre-title sequence. It is the complete opposite of the lackluster Toshiba commercial.

But the real star is John Richardson. His succession of almost seamless cuts between the real Acrostar BD-5J flown by Fornof and various models and miniatures of the plane still holds up today. Together, Glen and Richardson created one of the more tense flight sequences on film, even by 007’s standards.

- Heart of Stone: Female Bond-Clone References Moonraker, On Her Majesty’s Secret Service and Other Bond Films - February 8, 2024

- How Editor Peter Hunt Saved ‘From Russia With Love’ - January 27, 2024

- This Periodic Table of Tropes Is The Ultimate Storytelling Infographic - January 22, 2024