Revisiting Bruce, the Malfunctioning Animatronic Shark That Made ‘Jaws’ A Horror Classic

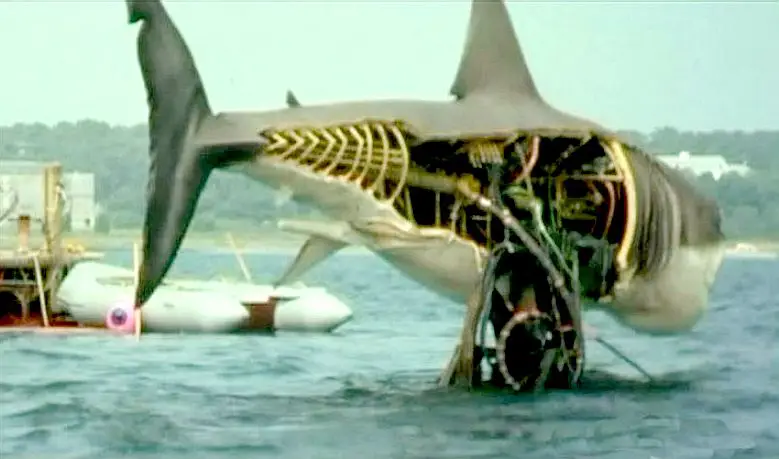

Bruce’s animatronic insides.

Jaws is a story about a shark that wreaks havoc and destruction on a small community, and the failure and, ultimately, success in defeating it. This is also, more or less, the same story behind the movie’s troubled production. There is a reason why the shark remains unseen for the majority of the film. That’s because “Bruce”, the animatronic shark, malfunctioned for the majority of the shoot. The mechanical shark was a menace that almost killed the production. Without a working shark, the 26-year-old director, Steven Spielberg, was forced to find a new way of creating suspense and terror that turned the camera into the shark’s POV.

Bruce still appeared in the film, but Spielberg relied mostly on his new technique. This suspenseful horror technique is often described as Hitchcockian, but it also owes much to cables, editing, and the talents of composer John Williams.

Here’s the full story about Bruce, and how Spielberg’s new technique scared an entire generation out of the water.

Building Bruce

The monster-sized 25-foot great white shark seen on film is an amalgamation of animatronic sharks and real-life footage. The crew shot the real-life shark footage off the coast of Australia. To give the illusion of the shark’s monster-size, a real 15 foot great white was filmed swimming around a miniature shark cage that housed a diminutive 4′ 11″ actor.

The animatronic sharks, on the other hand, were built to full 25-foot scale. Bruce, named jokingly by Spielberg after his lawyer, Bruce Ramer, was designed by production designer, Joe Alves, and constructed by Bob Mattey, who previously built the giant squid in 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea.

Spielberg rejected the idea of using miniatures. He wanted the sharks to be full-size, and fully-operational animatronics that looked and moved like the real thing. In addition, he opted to film the sharks in the open sea (previous films shot ocean sequences in water tanks).

The open sea helped with realism, but it meant nothing without a realistic-looking shark. Spielberg just needed one that worked. But no precedent existed. The only mechanical creature that came close was Mattey’s mechanical giant squid, but that beast’s giant body remained stationary in 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea; only it’s tentacles moved, which hardly compared to a shark moving through the water.

Alves had to devise the shark from scratch. He first drew large charcoal sketches based on the description of the shark in Peter Benchley’s novel to show the various actions the shark would perform in the movie. Then he did a sectional drawing of the shark. This cross-section of the shark from nose to tail showed Bruce’s artificial rib cage and the placement of Chromoly tubes used to house and protect pneumatic hoses that operated the mechanical creature.

However, convincing others of the shark’s viability proved difficult. “I interviewed a number of effects people, and I got basically the same sort of reaction,” said Alves.” ‘This isn’t going to work. A full-size, mechanical shark had never been created before.'” Despite everyone’s doubts, Bob Mattey convinced Alves he could build it.

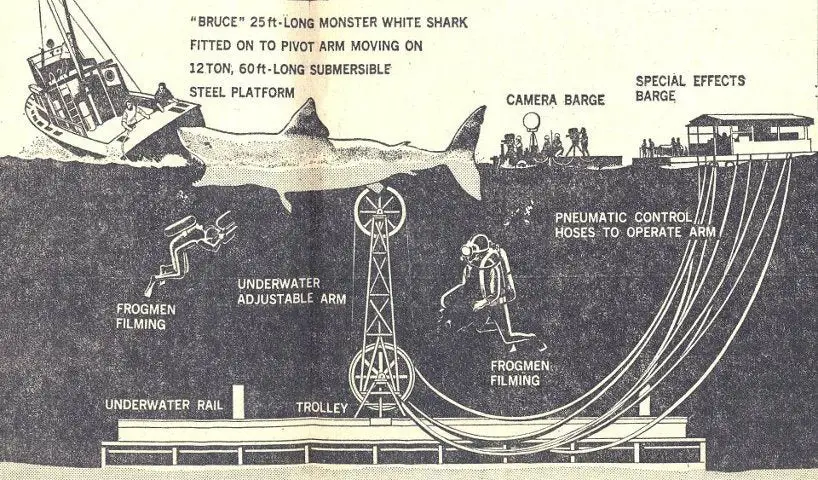

Bruce is a combination of three animatronic sharks: one that moved from left-to-right; another which moved from right-to-left, and a shark sled. The shark sled was an animatronic shark attached to a large arm that went back and forth along an underwater rail mounted to the seafloor. The crew moved this rig to various locations off the coast of Martha’s Vineyard to film the different scenes in the script.

The shark sled, which moved back and forth along an underwater rail mounted to the sea floor.

Each shark had a steel skeleton, hydraulics to open and close their mouths, and air-powered pneumatic mechanisms that moved various parts of their bodies. But there was a problem. These sharks just didn’t like saltwater.

That Sinking Feeling

The animatronic sharks were, quite simply, duds when submerged off the coast of Martha’s Vineyard. When the crew lowered the first shark into the water, he sank straight to the bottom. Bruce performed well in freshwater tests, but no one checked to see if saltwater would be a problem. It was. It corroded both the inside and outside of the shark and leaked into the pneumatic hoses. At best, the animatronic sharks were difficult to work with, and at worst, completely unresponsive for the majority of the shoot. These animatronics cost $500,000 to produce, which ate into the $7 million budget. And every day the sharks malfunctioned, they delayed the production and increased costs.

Spielberg nicknamed them the “Great White turd”. With a limited track record, the unproven director helmed an already troubled production, with the script undergoing daily rewrites on set.

Spielberg was forced to be creative. “I knew that it’s gonna take three or four weeks to rebuild the shark, and so we’d have to make up something else that didn’t exactly show the shark, but gave the sense the shark was near… the script was filled with “shark.” Shark here, shark there, shark everywhere.”

An Invisible Terror

Spielberg’s solution gave the film a level of suspense no functioning animatronic shark ever could.

Remember the iconic opening sequence in which the shark’s first victim, Chrissie Watkins (Susan Backlinie), is dragged back and forth before disappearing beneath the waves? We never get to see the shark, but the scene remains the most memorable one in Jaws. Spielberg, with the help of composer John Williams’ diabolical music score, begins with the camera moving up towards the swimmer’s feet. In a masterstroke of ingenuity, Spielberg uses the camera to simulate the POV of the shark, and in the process, craft one of the most terrifying movie openings. Not once do we get a glimpse of the shark. No fin, no tail. Nothing. But we do get to see Chrissie thrashed back and forth by an invisible terror. And what adds to the horror is the silence and stillness of the ocean after Chrissie is pulled beneath the waves–as if nothing happened.

Spielberg credits author Peter Benchley for the sequence. Benchley describes the attack in the opening pages of the novel, but never the shark. Our imagination fills in the gaps. The most terrifying shark is never Bruce, or footage of real-life sharks, but the one we never see. It’s the one crafted from the camera acting as the shark’s POV in combination with William’s score, John Carter’s sound mixing, and Verna Fields’ editing. What this conjures up in the imagination, terrifies the viewer more than any animatronic or real-life shark could. It elicits a psychology of terror.

“If the shark had been available visually, it might have changed the whole psychology of the experience,” said Williams. “When you hear, ‘boom-boom, boom-boom,’ you’ve already been conditioned to think that’s when the shark is present. When the shark is far away, it’s very faint. When the shark is just about to attack it’s very close and it’s very loud. We can advertise the shark’s presence or his attitude by how we manage these notes, just very few notes.”

Spielberg added to this psychology of terror by bringing the camera down to water level. “I really wanted this movie to just be at water level,” he said. “The way we are when we’re treading water. We don’t see water at three feet off the water.” The camera crew held the camera at water level in a water box, made especially for the film by Panavision. It was suspended on rafts so it would float. “This has a psychology about it that makes you aware that just below the surface of the water could be that shark.”

Note the specially constructed floating camera boxes in the background. Spielberg used them to bring the audience’s eye-line down to water-level, which gave a similar psychological effect to being in the water.

In addition, a specifically-designed rig was made so cables tied to actress, Susan Backlinie, could be pulled under the water, and left or right, to simulate her character, Chrissie, being helplessly and violently dragged through the water. Backlinie wore an orange u-shaped life preserver around her legs, which was cabled through a concrete block approximately a hundred yards away. When the cameras rolled, six to eight men ran up and down the beach with the cable, which pulled her violently through the water. Spielberg had another cable to pull himself.

“The first jerk-down, Steven did,” Backlinie recalled. “He had a cable that came to the front of my stomach and went to an anchor that was laying at the bottom of the ocean…and then he just sat and when he wanted that pulled, he just would pull.”

The experience was extremely painful for the actress. The terror seen on screen isn’t acting, according to the sound editor, Jim Troutman. Rather, it’s the moment she sustained injuries:

“For some reason or another, they [the cables] both went at the same time, and they broke some ribs. And she screamed. And when she screamed, she went underwater. And then she started saying, ‘Please God. Dear God.’ Like that. And the water was rolling in her mouth, and the word ‘God’ would come out every once in a while. She was hurting. I mean absolutely hurting. And we went with the one that really hurt her. And that’s the one that’s in the picture.”

Slowly Revealing More And More of the Shark

Bruce’s malfunction worked in Spielberg’s favor. Embracing this limitation, Spielberg built up the audience’s anticipation to see the shark. In successive attacks, the director recreated the suspense of the opening scene, beginning with shots of swimmers’ dangling legs under the surface. In scenes where there are multiple swimmers, the audience wondered which person the shark would attack, adding to the suspense.

With each successive scene, Spielberg revealed more and more of the shark. First, we see a distant shot of the shark’s flukes as Bruce rolls over when attacking the boy on the lilo. Then we see a dorsal fin as the shark enters the lagoon later in the film. That same scene culminates with a glimpse of Bruce’s head as he pulls a man under the surface. This culminates with the sickening view of the man’s severed leg sinking to the seafloor.

It is only in the third act that we finally see Bruce in all his glory when he launches out of the water onto the stern of Quint’s fishing trawler, the Orca. A terrified Quint, having survived the attack of hundreds of sharks after the sinking of U.S.S. Indianapolis in World War II, slides helplessly into the mouth of the monster shark moments before coughing up blood as the shark bites on his abdomen, signaling his demise.

Even in this final act of the film, Spielberg built up to that moment when Bruce launches out of the water, by using barrels to show the speed and strength of this unseen aquatic beast. “The barrels were a godsend because I didn’t need to show the shark as long as those barrels were around. What you don’t see is generally scarier than what you do see,” Spielberg explained.

The music, the flotation barrels, and the POV shots trace back to Alfred Hitchcock. Some call this a happy accident thanks to Bruce’s malfunction. Nonetheless, Spielberg demonstrated his mastery of cinematography and Hitchcock’s film-making tricks. That shot of Chief Brody (Roy Scheider) on the beach when he realizes the shark has struck again is no accident. Spielberg knew he could achieve suspense not only from the suggestion of an unseen shark but also from the reaction of the humans in and out of the water. The shot below is influenced by a similar tunneling effect developed by Hitchcock in Vertigo.

All these elements–particularly the restraint in showing the actual shark–is what made Jaws a classic of American film-making. Because let’s face it, Bruce looks damn fake up close, and it might have sunk Spielberg’s career if it worked according to plan.

- Heart of Stone: Female Bond-Clone References Moonraker, On Her Majesty’s Secret Service and Other Bond Films - February 8, 2024

- How Editor Peter Hunt Saved ‘From Russia With Love’ - January 27, 2024

- This Periodic Table of Tropes Is The Ultimate Storytelling Infographic - January 22, 2024