Syd Mead: The “Visual Futurist” Who Influenced Hollywood’s Most Futuristic Worlds

Syd Mead, concept artist, designer, and “visual futurist” died on 30 December, 2019. He leaves behind a ubiquitous presence in the world of science fiction, with his designs influencing some of Hollywood’s most breathtaking worlds.

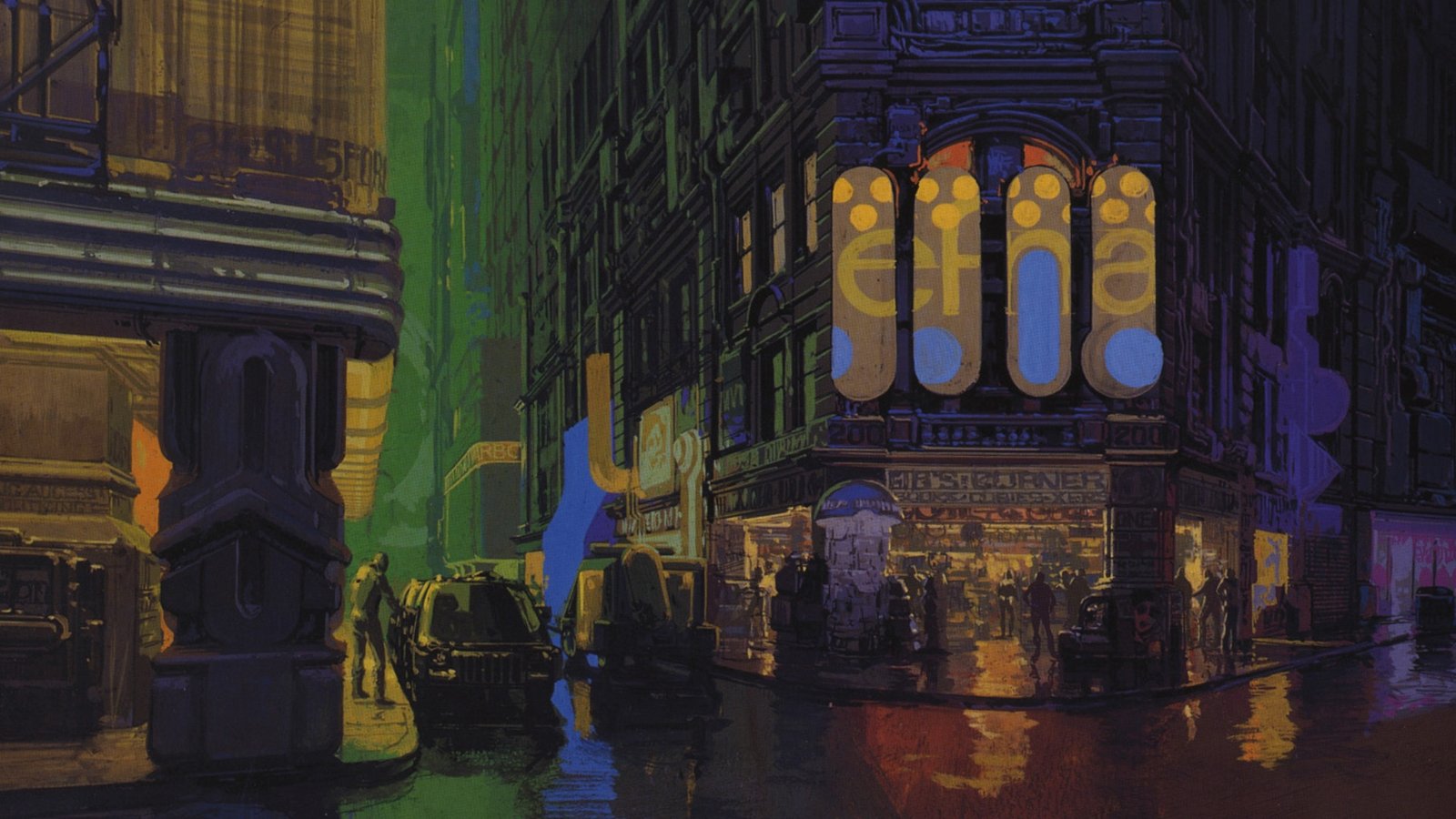

No future city-scape has been imbued with such a lived-in presence than Syd Mead ‘s Los Angeles of-the-future in Blade Runner. Despite its futuristic pyramidal mega-towers that dominate the skyline, and it’s flying vehicles, this futuristic take on LA feels like a real place. This is because Mead managed to ground the more futuristic elements in the modern-day, and give design functionality into the most futuristic vehicles.

Blade Runner is one of the highlights in Mead’s prolific career, which in Hollywood, included work on Star Trek: the Motion Picture, Aliens, Tron, and Minority Report–to name a few. But he wasn’t just limited to the movie business. His designs also extended to the real world, even if they were mostly a future projection on what Mead saw life to be like for humanity years from now.

He was self-proclaimed “Visual Futurist”. And the title sits well. He brought–to the best of any concept artist’s ability–a sense of science fact into the world of science fiction.

His death, at the age of 86, comes just a month before receiving the Art Directors Guild’s William Cameron Menzies Award during the Guild’s 24th Annual Awards ceremony on February 1st, 2020.

Tributes flooded Twitter, all giving us a retrospective of Mead’s prodigious design work.

No, not the master. Rest in peace Syd Mead.

His art and design mind influenced us all, not only other artists but the entertainment industry artistic essence; He changed practices and quality bar forever for better.

Thanks for inspiring us all. R.I.P. king futurist. pic.twitter.com/Peqf9y4Jlj— Davison Carvalho 🕷 (@colorblindmess) December 30, 2019

An Industrial Design Background

Mead’s first designs were for Ford, and U.S. Steel. By 1970, he founded his own design business, Syd Mead Inc., which designed a plethora of different products from architecture to restaurants, and companies like Phillips.

“His drawings for Phillips Electronics in the mid-’70s featured magnetic programmed learning capsules for junior college students,” Los Angeles magazine wrote in 2006, “and a three-dimensional home entertainment system that, had it ever been developed, might have proved superior to today’s high-definition TV.”

His designs of a futuristic Manhattan depict people using handheld devices long before smart phones were in use. His designs were not just fanciful, many had real-world applications.

Still, Hollywood was calling, and his talents went global when he worked as “production illustrator” on 1979’s Star Trek: The Motion Picture. His first feature film.

From there, Mead worked on some of the best sci-fi films of the ’80s: Tron, Aliens, and Blade Runner. A futuristic design of a four-legged transport for U.S. Steel even served as the influence for concept artist, Joe Johnston’s design of the Imperial Walkers (AT-ATs) in The Empire Strikes Back (1980).

Basing the AT-ATs on Mead’s drawing gave those lumbering mechanical beasts some plausibility in their design, especially the joints of the legs. His background in industrial design is always present in his sci-fi designs adding a sense of plausibility, which accounts for the timelessness of the designs and their longevity in popular culture. For instance, his futuristic bike in Tron, is designed from the ground up. Rather than just cool visuals, Mead thought about how the bike would actually function.

Mead even spotted a design flaw in the description of a drilling machine in the screenplay for The Core (2003). Based on Mead’s suggestions, director Peter Hyams altered the script.

Syd Mead ‘s Design Process

Mead explained his design process to The Boston Globe in 1985, when he said:

“All ideas go through three stages. The first stage is the idea itself. Thinking of that is a whole specialty in itself, because if something exists someone had to think of it.

After that the next stage is documentation. That can be anything from a set of sketches or an oil painting to a written description to a working model. The last step is manufacture. Making it real.”

Further details on his design process is evident in the book, The Movie Art of Syd Mead: Visual Futurist, which breaks up his work into different movies. It shows his thought processes, hand-drawn sketches and notes that even take into account small details, like Deckard’s keycard, or the look of ATMs in Johnny Mnemonic.

His final concept art is mostly painted in gouache, a thicker kind of watercolor. Everything was painted by hand, even when other concept artists turned to computers.

While his vehicles are intricately designed to sell their functionality, his city-scapes helped establish a film’s tone and style from Blade Runner to Steven Spielberg’s Minority Report.

In his tribute to Mead, Tim Soret, the founder of Odd Tales Games posted examples of Mead’s concept art of the streets in Blade Runner adding: “Without him, the visual language of science fiction wouldn’t have been the same.”

The Great Syd Mead passed away.

Without him, the visual language of science fiction wouldn't have been the same. Here, his vision for the streets of Blade Runner. pic.twitter.com/sDENt67w8z

— Tim Soret (@timsoret) December 30, 2019

In addition to his design work on two movie adaptations of Philip K. Dick classics, Mead is also the only westerner to do design work for Gundam, a popular anime. He also brought his futurism into designing the mask making machine in J.J. Abrams Mission: Impossible III.

But it seems fitting that Mead’s final movie design saw him return to his most famous world in Blade Runner 2049, creating the landscape of a future Las Vegas. Nonetheless, it probably won’t be the last we see of his work in film. No doubt ideas will be mined from his art, and if the project gets off the ground again, we may even see concept art from an unproduced remake of Forbidden Planet (1956) made into sets and props, which he created alongside the film industry’s other great concept artist, Ralph McQuarrie.